It feels as though the video game industry is in the middle of a transitional period. As the medium continues to expand and the number of games being published increases due to better distribution platforms, we are seeing the results of all sorts of interesting experimentation. Much of this experimentation has been happening at the narrative level, with experiences of all sizes being crafted, that place the same amount of consideration towards their themes as their game mechanics, resulting in a much higher standard of writing across the board. This felt more apparent than ever last year, with an abundance of sequels and original titles utilizing methods of storytelling that take advantage of this interactive medium.

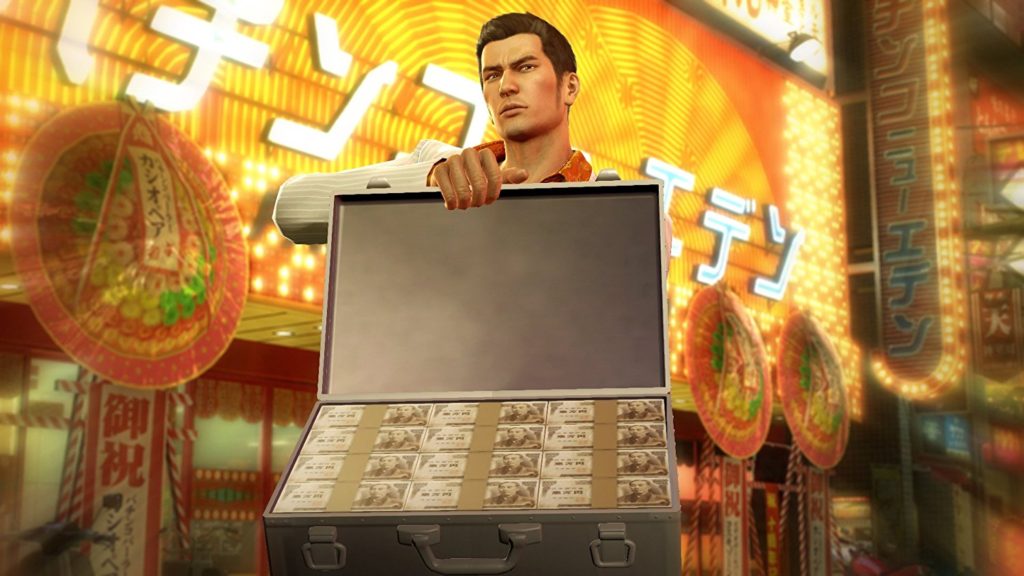

Yakuza 0

Yakuza 0 may be a continuation of a long line of narrative-focused games, but it has also been the entry point for many due to its nature as a prequel. My only regret is that I hadn’t been introduced to this wonderfully melodramatic crime tale sooner. We follow the trajectory of Kiryu Kazama and Goro Majima as they define their paths as young Yakuza. Both have either been sidelined or deceived by their perspective organizations, falling victim to the schemes of power players. One of the core ideas here is the refutation of blindly following leadership figures, as both Goro and Kiryu must make tough choices to preserve their moral identity despite their orders.

The plot is a winding page-turner, full of outrageous plot twists that don’t just exist for shock value, but instead paint a picture of complex people who consistently defy expectations. It is largely a story about family, or found-family more specifically, and the lengths people will go to protect their loved ones. There is such tremendous warmth to be found in these characters and their relationships, from the brotherly bond between Kiryu and Nishiki, to the connections Goro forms with his enemies turned friends. One of Yakuza 0’s most impressive elements is that it navigates the treacherous waters of tonal whiplash with absolute confidence, depicting the inhumanity of torture and humans trafficking one moment, while presenting outrageous telephone club dating sequences the next. Much of this works because of the multiple methods in which it delivers it’s story, using cutscenes during crucial plot moments and lengthy blocks of text during much of the side content, creating a natural barrier between its humor and drama.

Because of this it can blend the Shakespearean overtures of the main story with side missions that offer a consistent steam of hilarious goofy antics. Much of the optional content feel like a satirical tour of the more bizarre aspects of late 80’s Japanese culture that entertains with visual humor as well as sharp writing. Oh and did I mention there’s really, really good karaoke scenes? And a chicken that can manage your real estate firm. This one’s a keeper.

Night in the Woods

One of the most exciting elements of the indie scene gaining such prevalence in recent years is that gaming now represents points of view that never would have appeared in mainstream AAA titles. Night in the Woods is an excellent example of this, portraying a group of 20-somethings living in the middle of rural USA. The game begins with Mae returning to her home town after dropping out of college, a fact which her family isn’t thrilled about, but is accepting of none the less. Mae and her friends live in a decaying mining town surrounded by nothing, coloring their perceptions of the world and giving them little to look forward to besides escape. For the many who have grown up far away from Middle America or their own country’s equivalent, or for those who have, it’s a humanizing portrayal of what it’s like to live in a region characterized by economic downturn.

Night in the Woods also blends the metaphysical, a mystery plot line, and the trials and tribulations of these millennials into an intriguing multi-dimensional story. The writing here is top-notch, presenting exceedingly vivid portrayals of these disgruntled humanoid animals. The chemistry between this friend group is palpable, a great recreation of how conversations between old friends play out. Gregg in particular is one of my favorite characters in recent memory, his wiggly arms, and frequent references to “crimes” marking him with a hilarious sense of specificity. The protagonist, Mae is also well defined, and while she isn’t as immediately likable as some of the other characters, her inner-conflict and problems are delivered deliberately, but effectively. While some of it’s more overly philosophical elements don’t entirely work, the politics that emerge from the mystery plot-line are exceedingly well-considered and relevant, dialing into the desperation that gives rise to certain extreme leanings.

Doki Doki Literature Club

If meta-textual visual novel dating/horror games are more up your alley, Doki Doki Literature Club is an excellent (and free) choice. You star as a blase archetype of an anime protagonist who is dragged against his will into his High School Literature Club. Upon entering, he is surprised to find that the club entirely consists of cute girls, and solemnly vows that he will try his best to date one of them. From there you are treated with typical, but admittedly charming interactions with the Lit Club member of your choice, slowly building a relationship through your decisions. But DDLC wouldn’t have taken the internet by storm if it merely existed in the well-worn mold of a dating sim.

*Warning: Minor spoilers as to the nature of DDLC*

The true nature of the game begins to reveal itself through poetry. As per the club president’s orders, each club member is required to prepare something for each meeting. This is how you court the romantic interests, tailoring your poem to the tastes of the person you’re trying to date. However, it’s through the girl’s writings that you are clued in that something is awry, their prose giving vague hints into the reality of the situation. Their poems begin as mildly unsettling or melancholy in tone, but gradually builds towards increasingly desperate pleas for help. When the traumatic twist finally occurs, things fully plunge into psychological horror. The fourth wall is blasted apart, and not in a tongue-in-cheek fashion. Instead the full force of reality hits these characters with the force of a train, making the player consider the implications of their actions.

DDLC simultaneously comments on the contrivances of dating games, harem anime, and the very nature of this sort of wish fulfillment. While the plot twist seems glib and somewhat insensitive at first, by playing through all of the endings you’re able to reveal the game creator’s empathy for all parties involved: those who enjoy the type of game being satirized, and for the characters who are thoroughly abused. While you could still argue that it merely uses its cast as props to convey its ideas, the horror of DDLC wouldn’t work if players didn’t connect to the characters. They may be firmly and intentionally routed in cliche, but the members of the Lit Club are quite endearing, making the nightmare they suffer all the more affecting.

*Spoilers end*

Wolfenstein II: New Colossus

While games that center around shooting people in the face usually don’t have the most compelling stories to tell, the previous two Wolfenstein games have recast a series of mechanics-first shooters into something that does just that. Continuing the tale of BJ Blazkowicz, New Colossus casts an alternate history in which America has been overtaken by Nazis. But instead of the bastion of democracy fighting tooth and nail for their time-honored ideals, they roll over, finding a great deal of compatibility with the Third Reich’s notions. While this concept might seem shocking or implausible, witnessing pre-Civil Rights America sell out racial and ideological minorities to the fascists doesn’t feel like too much of a stretch.

But beyond its premise, New Colossus delivers a fateful meeting between absurd B-movie schlock, and a more character-centric story. BJ has been gravely injured from the events of the previous game, spending much of the title grimly accepting his inevitable death, and the fact that he will never meet his unborn children. Instead of a cigar chomping action hero, we are treated to a humanized rendition of a character that used to be a scowling sprite in the bottom left corner of the screen. While it never forgets to address the tremendous strain our freedom fighters find themselves subjected to, it also lays out some of the outrageous sequences I’ve ever seen in a video game. And despite the utter insanity of these moments, the plot mostly feels cohesive. Although the final act drags somewhat, Machine Games has proved once again than an interesting story with thematic meat can be told in the context of an FPS.

Nier: Automata

In my opinion, Nier: Automata not only had the best narrative in a game last year, but it may be the most thematically rich game from any year. Yoko Taro has further shown that auteurs can exist in the game industry, constructing a work that comments on the nature of its form. It stars 2B and 9S, androids who are part of a military organization known as YoRHa. YoRHa is the last line of defense for humanity against a robotic alien invasion, with the last humans having fled to a base on the Moon. While the premise makes it sound like a cartoonish sci-fi escapade, it isn’t long until morality begins creep into the picture.

*Warning: minor spoilers ahead*

Automata is largely a game about the nature of cyclical violence. It profiles how this organization routinely demonizes its enemies, conditioning the members of YoRHa to blindly fight their sworn foe through extensive propaganda. This thematic footing allows the game to directly deal with the problems of ludonarrative dissonance, that is, the disconnect between gameplay and storytelling that characterizes many game franchises By dwelling on the fact that the player is implicated in acts that essentially equate to mass murder, we are forced to question why the medium so frequently has a disposition towards violence, and more broadly why this seen as acceptable.

The idea that these androids are so desperately fighting for something that doesn’t even directly benefit them ties into another core conceit, the idea that the quest to find purpose in life can be all consuming. While the androids fight and die endlessly for what amounts to nothing, they do so because the alternative is more horrifying; a life without meaning. This is also explored in the comedic side-missions, in which the machines and androids that dedicate their entire being towards a single goal are consistently met with ruin.

Although the characters that fall victim to obsession are met with self-destruction, this isn’t meant to lazily affirm that life is meaningless. In the brilliant conclusion, the player is forced to decide where they stand, either helping continue the pursuit of purpose and meaning, or to end the cycle altogether. The sacrifice necessary plays with our psychology as gamers, using the attachment we’ve formed to our character profile as a weapon. We may be flawed, drawn like moths to flame over the faintest glint of meaning, but if we keep trekking on, accepting that failure is inevitable and necessary, that there is no one universal purpose to our lives, then we might just make it.

*Spoilers end*

Not all aspects of the plot are perfect. Its final act feel somewhat rushed, largely due to its lead feeling underdeveloped unless you find the optional text logs that explains her past. It’s wrapped in enough anime-inspired flourishes to dissuade some, and the potential fan-service surrounding 2B is very disappointing. But the fact of the matter is that I’ve only scratched the surface of Automata’s thematic content. This story is delivered in a riveting fashion, abusing our perception of the situation to deliver crushing blow after crushing blow. To say that I’m looking forward to Yoko Taro’s next game is an understatement.

Other Quick Mentions

The previous five games were just a few of my favorites from last year, and there were far more stories worth discussing that were released in 2017. Finding Paradise continued Freebird Games’ To the Moon series, once again offering a melancholic tale about addressing death and celebrating life. Pyre blended sports gameplay with a visual novel, portraying a band of misfits’ battle for redemption and freedom. Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice allowed Ninja Theory to further experiment with the form, constructing an empathetic journey through the mind of an unreliable narrator. We’ve already written about What Remains of Edith Finch in length, but Giant Sparrow introduced us to a cursed family while ultimately presenting an uplifting message. Another walking sim,Tacoma, used the interactive nature of games to construct a naturalistic series of conversations that could be absorbed non-linearly, which painted a well-characterized future marred by corporate corruption. And Detention gave us a haunting glimpse into Taiwanese folklore, creating dread through a combination of Cold War-era paranoia and the supernatural.

There’s no denying that there is an abundance of interesting stories being told right now, both in the AAA space and the indie scene. Even if publishers are scrambling to actively dismiss the notion that games mean anything, this is just a naked attempt to side-step controversy. While a vocal minority may want games to remain fun toys that are devoid of any political or thematic context, game developers will continue to push the envelope by further utilizing this interactive art-form’s unique strengths to tell a great story.