When it comes to video games, one of their best and worst qualities is their tendency to change. Dictated by shifting tastes, developer interests, and better hardware, genres come and go in an endless cycle. These shifts are often propagated by popular titles that create whole new styles of play and give rise to droves of copycats. The PS1’s catalog was defined by JRPGs, the 360 and PS3 era was dominated by first and third-person shooters, and we currently live in the age of games as a service, MOBAs, and Battle Royales.

Although it could be argued that game design has largely improved over time, a fact that feels evident when returning to many (but not all) older titles, the unfortunate side effect of this constant forward march is that certain sub-genres get lost in this shuffle. Whilst there are certainly long-running franchises that are testaments to what came before, even these tend to constantly reinvent themselves. And sometimes these beloved series end up becoming the progenitors of these large-scale genre shifts.

Whilst these transitions can often be groundbreaking and breathe life into stale gameplay, even in the best-case scenario something is lost. Beyond just the clunky charm of many older games, there are multitudes of subtle design decisions that make these titles unique even in a modern context; things that are memorable and weird and novel. It’s hard to think of a better example of this than Resident Evil, a series that birthed not one but two styles of game and that tends to morph much like the grotesqueries at the heart of its stories.

Resident Evil: The Birth and Death of a Genre

When Resident Evil was released for the original PlayStation back in 1996 it was a veritable sensation. Tasking players with exploring a dense mansion full of undead monsters whilst carefully rationing a limited pool of resources, the game popularized what would come to be known as survival-horror. Presented via fixed-perspective shots, its dutch angles and claustrophobic compositions presented a disarming mixture of B-movie camp and genuinely unsettling material. Inspired by earlier games like Sweet Home and Alone in the Dark, Resident Evil combined adventure game elements with heavy dosages of terror and inspired a horde of like-minded titles such as Silent Hill, Fatal Frame, and Haunting Ground.

Then in 2004, the series underwent a paradigm shift with Resident Evil 4. The game was a massive critical and financial success, so much so that it would entirely alter the trajectory of the franchise. Ditching the fixed-camera angles of its predecessors, its over-the-shoulder perspective would become the standard for third-person shooters. This switch in camera angles mirrored a switch in gameplay emphasis, the small-scale zombie encounters of the previous titles replaced by large shootouts with droves of infected cultists.

Gone was the plodding exploration and the heavy emphasis on inescapable terror, replaced by the high-octane bombast of a thriller. Acting as the pallbearer for the genre it helped create, the series’ new emphasis on action was mirrored by its contemporaries. Although a few smatterings of the genre would be released in the coming years, such as Dead Space, broadly speaking survival-horror drowned in a sea of fast-paced shooters.

Survival Horror is Back… Or is It?

But eventually, the pendulum swung back. After the series bottomed out with Resident Evil 6, Resident Evil 7: Biohazard was a welcome course correction. Inspired by non-confrontational horror games like Amnesia: The Dark Descent, Resident Evil 7: Biohazard combined puzzle-solving, resource scarcity, and a de-emphasis on shooting things. Although somewhat different in feel than the original trilogy due to contemporary influences and its new first-person camera perspective, it was the closest the series had looked like its roots in a long time.

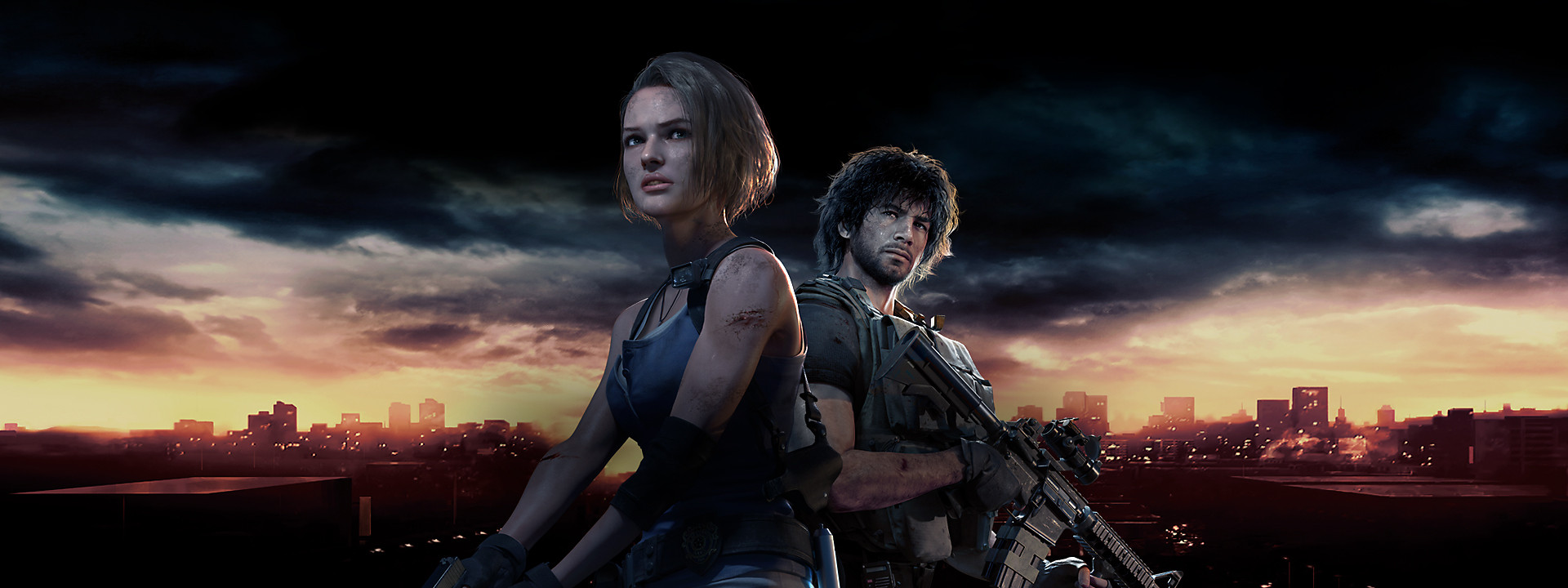

This mini-renaissance continued with last year’s remake of Resident Evil 2, a brilliant melding of old and new that combined Resident Evil 4’s third-person shooting with exploration and a focus on instilling terror. Completely rehauling the original game’s mechanics from the ground up, it managed to find a near-perfect balance between scares and thrills, marking the reanimation of a mostly dead genre. For a moment it seemed possible that a new golden age for survival-horror was upon us, with a remake of Resident Evil 3: Nemesis announced shortly thereafter.

However, it seems like this new golden age may not come to pass. A few weeks ago the Resident Evil 3 remake was released, and whilst in many ways it is a competent game in its own right, it doesn’t continue the design philosophies of its predecessor. This is a little confusing on the surface, as there is a strong resemblance between the two. Both games were built in the RE Engine, utilizing similar assets such as UI elements, enemy types, and even certain environments. The gunplay and movement feel roughly the same. Allegedly, it was initially planned for these two remakes to be released in a single package and they were developed in tandem. Hell, even the original games were relatively similar to one another and were also released roughly a year apart, implying that these games would mirror this trend. But the fundamental difference between last year’s remake and this year’s is how they balance their elements of action versus their elements of horror. To put it simply, Resident Evil 2 is a modernized example of survival-horror, whilst Resident Evil 3 is a third-person shooter with a light dusting of the genre.

So why does this matter? Why is Resident Evil 2 one of the most memorable games of the console generation, while Resident Evil 3 is only luke-warm comfort food? Why is it that I can recall large chunks of the latter with near-perfect clarity where the former has largely faded out of memory and out of the zeitgeist after just a few weeks? What is so essential about survival-horror, and more specifically, the successful application of the genre’s principles in Resident Evil 2? Well, the first answer to that question is a matter of setting.

Claustrophobia and Tension

Resident Evil 2 largely takes place in the labyrinthine halls of the Racoon City Police Department, a refitted art museum that is both mundane and unnerving. Its tight corridors, maze-like layout, and secret compartments inspire a macabre mixture of dread and curiosity. The constrained nature of this space causes a pressure-cooker effect, tension escalating unbearably each time you round a corner. These tight corridors create a terrible intimacy, grasping limbs reaching out of hidden alcoves, ruined visages greeting your progress.

By comparison, Resident Evil 3′s locales are far more open. Traveling through the streets of Racoon City doesn’t inspire the same feeling of constant dread, as you can generally see your shambling foes long before they see you. This means that instead of staring death in the face, you can take pot shots from a safe distance. Because you aren’t constrained in tight corridors, Resident Evil 3‘s difficulty is artificially bolstered through a higher zombie count. Instead of feeling cramped, claustrophobic, and vulnerable, mowing down waves of zombies feels perfunctory.

When properly executed, one of survival horror’s hallmarks is that every encounter is rife with tension due to the feeling that you are horribly disadvantaged. By making us feel trapped with unflinching monsters, the halls of the RPD make every zombie fight an adrenaline rich-crescendo that punctuates the long melodious stints of exploration. By comparison, the numerous locales of Resident Evil 3 don’t make much of an impact. Acting as the backdrop for a series of functional but forgettable shoot-outs, the wider streets and cargo depots allow tension to dissipate like a leaking balloon. On top of making combat feel less like a life-or-death struggle, the world of Resident Evil 3 also provides little room for exploration, puzzle-solving, and downtime.

Detective Work and Backtracking

Great horror stories tend to follow a certain tempo, gradually building suspense to deliver a devastating scare. For this to be most effective there needs to be ample build, gaps in time that stretch on unbearably. For video games, this can be accomplished through mixing in other flavors of gameplay besides just shooting.

As it the case with many survival-horror games, Resident Evil 2 solves this problem with adventure game inspired exploration elements. The RPD and the game’s other locations are full of locked doors and cryptic mechanisms that thwart your progress. To escape this space you have to poke and prod at its many nooks and crannies, uncovering important items (usually obscurely named keys) that allow you to move past previous dead ends. This emphasis on backtracking is rewarding, inspiring a grim curiosity as you problem-solve out of your mouse maze. Even though creeping horrors await each turn of the key, there is a kind of empowerment that comes from unspooling this malicious world thread by thread.

Another benefit of this backtracking is that it builds familiarity with the world you explore. Ironically I have a morbid affinity for the halls of the Raccoon City Police Department, its corridors seared into my mind, its identifiable landmarks transforming it into a tactile, genuine place. And although you are frequently retreading your steps through “safe” areas that had been purged of monsters, the game defies expectations frequently enough to make even the familiar remain menacing. All of these strengths further heighten the mood and atmosphere and aid in the build of suspense.

Whilst Resident Evil 2 subtly guides us through a web of clues to make us feel like a detective, Resident Evil 3 brutishly shoves us in a straight-line, assault rifle in tow. Dashing through the streets of Racoon City, we are barely given enough time to construct a mental picture of our surroundings before we move onto the next place. Although Resident Evil 3‘s first area is probably the best at inspiring exploration and creating a sense of space, we generally aren’t given enough time to absorb what is around us. This undermines a sense of mounting tension and makes the gameplay far more one-note than its predecessor.

All of this combines to create an undeniable contrast between these two titles. Resident Evil 2 is a winding horror experience that concocts a miasma of dread through its excellent world design, Resident Evil 3 is a fairly straightforward shooter. Truth be told all of this would be much more palatable if A) there wasn’t such a dearth of games like Resident Evil 2, and B) if Resident Evil 3‘s action sequences didn’t come with so many caveats.

Not So Much A Case of Alien to Aliens

As a big fan of both action and horror, one of my favorite sequel pairings in film history is Alien and Aliens. Alien is a near-perfect horror movie, layers of foreshadowing, clever worldbuilding, and immersive set-design placing us firmly in the unfortunate shoes of doomed space-truckers. Aliens is similarly excellent, flipping the script on the empowering muscle-laden action flicks of its era. Both are exemplary examples of their respective genres, and Aliens manages to maintain much of its predecessor’s identity despite its different shape.

I wish I could say the same about Resident Evil 2 and Resident Evil 3. Although the latter holds up its end of the bargain, Resident Evil 3 is at best a moderately entertaining action game. Early on it manages to strike some balance between evoking fear and empowerment, but this eventually crumbles as your weapons grow dramatically stronger, and your ammo reserves swell. And although the inclusion of a new parry mechanic is a fairly brilliant stroke that makes boss fights far more engaging, vestigial elements from its predecessor hold it back as a shooter.

In Resident Evil 2, you never really know when a zombie is dead. Even when seemingly incapacitated, they can suddenly re-animate, a startling shriek accompanying their unholy rebirth. This ratchets up the suspense, making it tough to discern when to let your guard down. This mechanic remains in Resident Evil 3, but here it comes off as more of a severe annoyance than a well-employed tool for crafting tension. After clearing out hordes of zombies you must either patiently wait for each to revive, or methodically dump rounds into the apparent corpses. In more chaotic struggles this methodical approach is impossible. As a result, I probably took more damage from irritating ankle-biters that acted like trip-mines than I did from anything else. Perhaps even more frustrating is the fact that you can’t use the rewarding new parry mechanic on these foes, meaning that you either have to waste ammo, wait out their revival, or simply barrel through. Another annoyance is the lengthy animations that play out each time an enemy gets you in their clutches. Due to the higher enemy count, sometimes one zombie would finish its assault only for another to take its place, my character becoming a buffet for a congo line of undead ghouls.

These types of problems are mirrored by the enemy design. Since you are provided with more ammo and more powerful weapons, it is natural to assume your decaying adversaries would be proportionally nastier. Unfortunately, this bump in difficulty was largely achieved through introducing a variety of one-shot kill enemies. The lumbering Hunter Alphas swallow you whole, and the Hunter Betas will slash your throat if given the chance. Even though the Alphas are appropriately slow, fighting the Betas often feels like a crapshoot because of their speed. Sometimes they seem to charge, claws bared, and unceremoniously murdering you in an instant, and at other times they act with more trepidation.

Because of all of these issues, I found myself dying more often than I did in the previous game. Whilst mastering a game’s systems and overcoming steep challenges can be extremely rewarding, many of these deaths felt abrupt and unfair. And perhaps more importantly, the more frequent deaths have the adverse side-effect of completely deflating an atmosphere of horror. Games in the genre have an ironic problem that if they are too challenging and deaths occur too often, the player starts to feel desensitized to dying. This starts to break immersion and shatters the illusion that you should care about coming to a grisly fate. But as damning as this is, there is still one final nail in the coffin for the prospect of Resident Evil 3 as a horror game.

From Hunted to Hunter

It’s quite telling that the Resident Evil 3 remake chose to drop the original’s subtitle. Where Resident Evil 3: Nemesis featured its titular zombie hitman far more prevalently, its remake mostly relegates his presence to cutscenes. Like much of the rest of the game’s highlights, the best usage of the legendary baddie comes in its opening hours. After Nemesis’ introduction, the lurking behemoth exists as a constant threat in the back of your mind. This creates an undercurrent of anxiety through the early stints of exploration, and it’s hard to avoid imagining his shadow in every forlorn alley you come across. When he finally picks up on your trail, it makes for one of the game’s best sequences, a desperate escape through the streets you had just been exploring. This section works as a great slice of action horror, upping the body count without ditching cold-sweat inducing terror. But from this point on Nemesis’ appearances are limited to scripted chases and boss fights, failing to deliver the same dynamic feel of this initial encounter.

The most confusing element of this is that Resident Evil 2 had already set up a great blueprint for this type of persistent enemy with its usage of Tyrant. Appearing unexpectedly, this mysterious figure stalks you, his distant footsteps inspiring curdling anxiety. Although it would have been difficult to balance Nemesis’ ferocity to avoid making him too disruptive, it feels like a missed opportunity that there is only one stretch where he feels genuinely horrifying. Once you realize the chase scenes are scripted and predictable, the sense of terror surrounding the baddie deflates. Whilst Nemesis’ boss fights are generally well constructed and greatly benefit from the new dodge mechanic, his inclusion would have been more memorable if he made us feel truly afraid.

An Uncertain Future

To be frank, I enjoyed a lot of my time with Resident Evil 3 despite its myriad flaws. The opening sequence feels like an only slightly diluted microcosm of the previous game, featuring resource-scarcity, exploration, and some engaging encounters. At times it delivered on the type of oppressive paranoia mixed with rewarding action that makes this series so special. But taken as a whole it felt like a slight version of its much more impressive predecessor. Between its short length, lack of gameplay variety, uninspiring world-design, and a dearth of tension, it is dwarfed by Resident Evil 2 at every turn. And perhaps most disappointing is what this all means for the future.

The one-two punch of Resident Evil 2 and Resident Evil 7: Biohazard felt like a triumphant return for a dormant genre, but who knows if this trend will continue. If the circulating rumors are to be trusted, Capcom seems intent to return to the series in the immediate future. The company reportedly has a 2021 timetable for Resident Evil 8, which will continue Resident Evil 7‘s story, and a 2022 timetable for a Resident Evil 4 remake. Although a direct follow-up to Biohazard is quite tantalizing, it will be interesting to see how the company reinvents what is perhaps their most beloved game.

Although the Resident Evil 2 remake was a satisfying union of shooting and survival-horror elements, if Resident Evil 3 is any indication, the remake of the fourth game may not even attempt to strike this balance. In a medium that is memetic as they come, will Resident Evil 2 and Resident Evil 7 be enough to spawn a new golden age for this type of game? Or will Resident Evil 4 once again brush away its predecessors, reaffirming the popularity and dominance of the shooter genre? In light of the latest game, I’m not particularly optimistic about the future of survival-horror.

And just to be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong with action games. Both Alien and Aliens are great despite their fundamental differences. The issue is that in the gaming space for every game that aspires to be the next Alien, there are thirty more that aspire to be the next Aliens. Shooters can be engaging, important, and rife with tension. But it would be nice if more games fully utilized foreboding exploration and the management of dwindling resources to capitalize on this medium’s unique capacity for horror. It is yet to be seen which of their remakes Capcom will emulate in the future, but it would be nice if the series which introduced the principles of survival-horror to a wider world would continue to carry the torch.

Because whilst unnerving, stressful, and a little bit gross, survival-horror gives us the tools to fight back against a world that is uncertain and sometimes malicious. It gives us the courage to come to terms with our inherent fears in a controlled environment. And in a world that is increasingly defined by uncertainty and fear, it would be nice to have an avenue to face the world’s horrors head-on.