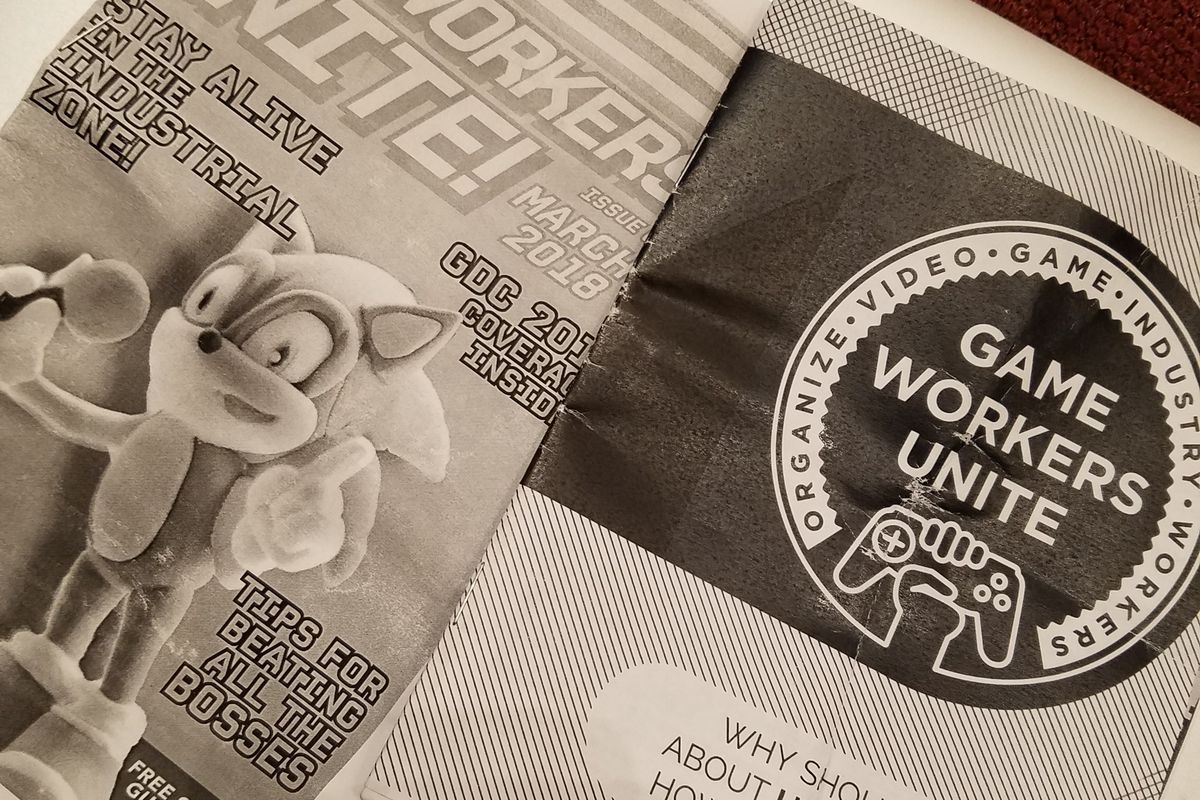

Game Workers Unite

We’ve all gotten excited over the prospect of playing a new video game, waiting patiently (and sometimes rather impatiently) for the day of its release. We play for hours, taking in the adventure, the scenery, the characters, and the story line, going at our own pace. Once it’s over,, it can often leave us wanting more, hoping that the next game isn’t years away. What we might not realize, though, is the amount of time game developers put into the games we love so much, and some of the sacrifices that are made to give us the game on its promised release date.

Take Rockstar’s newest game “Red Dead Redemption 2” out October 26, as example. In a recent article by Vulture, the co-founder of Rockstar, Dan Houser, admitted that developers had spent “several 100-hour weeks” working on the game in the last year. Such a story wouldn’t be surprising, considering RDR2 has 60-hours worth of content in the story line, with 500,000 lines of dialogue, and a file size of over 100 GB for both Xbox and PlayStation.

Since Vulture’s story hit the Internet, Houser went back on his statement, explaining to The Verge, that the occurrences of 100-hour work weeks happened briefly with the team creating the dialogue for RDR2, and it was their choice. Even still, many were concerned.

A lot developers working with other studios took to Twitter to voice their concerns and share their own stories regarding the “crunch-time” problem in the video game industry. This concept isn’t exclusive to Rockstar, and usually occurs when overly ambitious projects with very small teams are quickly approaching deadline, especially in the last few months before a video game’s release. Such strenuous work practices can be harmful to employees, both physically and mentally.

While some Rockstar employees dispute feeling “overworked” on RDR2, it is a feeling that Techland employees working on Call of Juarez: The Cartel were all too familiar with prior to the game’s 2011 release. In an article by Game Informer titled “Crunch: The Video Game Industry’s Notorious Labor Problem”, Techland’s multiplayer programming lead, Krzysztof Nosek described his mental state during “crunch”.

“Imagine excessive partying for a few days, or marathoning a video game for a few weeks straight when you were younger. You get tired, feel dizzy, behave a bit weird. Quite often you smoke, drink, eat, or take other mindless distractions, so your concentrated bursts of focus take a hit,” he explained.

The effects of a work “burnout” can take a bit to manifest, but what Nosek described is definitely a result. Those experiencing it have reported feeling anxious, depressed, angry, loss of appetite, exhausted but not able to fall asleep, detachment, and ill, according to Psychology Today. The longer the “crunch” is, the worse the symptoms can become.

“Longer crunches turn me into a mindless zombie. I don’t care about anything else in my life other than going to work and trying to get the project finished,” said Pawet Zawodny, head of production and chief operating officer for Techland in 2010.

A spouse of an Electronic Arts game developer gave a perspective on the other sides of things, in a LiveJournal post: watching her significant other work up to 12 hour days, seven days a week, during a crunch time, as they “complain of a headache that will not go away and a chronically upset stomach”. She brings up an interesting point though, that no matter how long her partner worked, the company was having to fix just as many problems as they were adding new material to the game.

Getting the work done in a shorter amount of time isn’t always better, and the International Game Developers Association proved it. According to the IGDA, “crunch mode slows development and creates more bugs when compared with 40-hour weeks”. This is because productivity in people is maximized at a five-day, 40-hour work week. The quality of work after 40 hours in a week begins to exponentially decrease after that. Despite this data though, a survey conducted by IGDA in 2015 said that 62 percent of game developers admitted they had experienced crunch time.

It’s hard to imagine why anyone would willing subject themselves to a job that asks for so much of their time and dedication. Why work the overtime if you know you’re not going to accomplish anything extra? Why work yourself until you’re exhausted, you can’t eat, and you can’t sleep? A lot of it has to do with the passion that comes with the work.

“I wanted to work in video games. That’s the dream. So I didn’t let anyone see and I did the work,” said Jared Rea, whose first job was as QA tester for Atari. He told Digital Trends that he’d work from 7AM to 11PM, not including the two-hour commute to and from work.

“I have mixed feelings about working overtime because I don’t feel like any company should ask people to sacrifice their lives or their health to maximize shareholders profits or whatever, but when you really love something…I have indie film friends…and I have a couple friends that write novels. I can tell you, just like in video games, when you are into it those people push themselves,” said Harvey Smith, co-creative director at Arkane Studios, in an interview with Game Informer.

It’s clear that there is a very defined labor problem in video game development, and those who have worked crunch time have spoken up about it, but what more can be done? The outrage on Twitter about Rockstar employees clocking in at about 100-hours a week some weeks is warranted, because crunch time shouldn’t be a celebration of passion, it should be marked as a failure on the part of video game companies.

It’s not always easy to remember the work that goes into the video games we love, and it’s easy to get disappointed when delays happen, but it’s important that gamers remain understanding of developers who need a little more time to perfect the games they make. It’s also important that game developers continue to share their stories, and even work with organizations like Game Workers Unite to rally for better working conditions in “the crafting of a unionized game industry”. Video games are a passion to all who are involved, whether in making them or playing them, and that passion shouldn’t be preyed upon by game companies.