It’s been eight years since the release of Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption, an ambitious open world game that applied the GTA model to a Western setting. Over that eight years, the studio has been working on a follow up, and for the first time in Rockstar’s history, the game required the efforts of each of the company’s disparate studios from across the world. The enormous human cost has been well-documented at this point, with controversy surrounding the absurd workloads that were required to complete this ambitious project.

As is the case for many games that are created over the span of many years, this long development cycle has manifested as both a blessing and a curse for the end product. The years of concerted labor are readily apparent in ways that make the game feel truly singular; the world is both massive and feels meticulously designed, the central narrative is a lengthy affair that boasts the studio’s most nuanced writing to date, and due to the fact that it was largely developed in a bubble, it diverts from certain trends in open world games that have become cloying due to their prevalence.

But RDR2‘s nature as a sequel to an eight-year-old game also has negative effects on many aspects of its gameplay. Even in 2010, the original RDR‘s third-person shooting mechanics felt somewhat archaic compared to some of its contemporaries, and its sequel retains these problems in a gaming landscape where fluidity and responsiveness in shooter games has become the expectation. A combination of heavy animation priority and input latency result in character movement that feels as though you are wading through molasses. Precise actions often become a frustrating gambit that doesn’t always result in the intended action.

Additionally the control scheme is weirdly convoluted, requiring unintuitive combinations of button presses. For some reason the button to aim your weapon is the same button that is used to focus on NPCs for peaceful interactions, which led to many accidental hold-ups. And this isn’t the only input that can easily lead to unintended violent actions. Under my control, Arthur Morgan has tackled random pedestrians while trying to mount his horse and shot shop keepers while attempting to trade them some pelts. He’s accidentally run over bystanders and been part of fatal horse crashes. All of this would likely come off as more endearing than frustrating if it weren’t for the draconian punishments that are enforced for criminal activity.

Unlike previous Rockstar games, once you’ve been spotted disregarding the law you will have a bounty placed on your head, and the more expensive bounties can only be removed by paying a fine. While this system usually works as intended the fact that accidental crimes incur a lasting punishment is frequently frustrating due to the finicky controls. Unsurprisingly the clunkiness of the general movement also carries over to much of the gunfights. In addition to fine movement feeling sluggish, getting into cover that sucessfully protects you from enemy fire is a dicey prospect, as many objects that you can hide behind don’t entirely cover your body.

The lack of rapidity in player actions is mirrored by fairly languid pacing throughout most aspects of the game. The slow buildup towards interactive segments in the first chapter, the lengthy introductions to story missions in which you must trek to the objective, the substantial amount of time it takes to skin an animal or to cook a meal, these aspect all accumulate the tedium. While all of these decisions were made for the sake of immersion, they will undoubtedly try the patience of many.

Although RDR 2 is a blockbuster video game which will likely sell tens of millions of copies, it also has some glaring gameplay flaws that will likely prove too much for many players. Its core movement and gunplay lack responsiveness, which is somewhat problematic considering nearly every story mission ends in another shootout. Its economy becomes broken as certain story missions flood your wallet with cash. The sluggish movement combined with a lack of leniency towards player conduct result in many unwanted confrontations with the law.

However, in spite of these glaring issues, the fact remains that Red Dead Redemption 2 does certain things so well, and in a fashion that this is so unprecedented, that many of my initial gripes melted into the backdrop over my numerous hours with the game. While modern open world games have largely been following the Ubisoft model, popularized by the Assassin’s Creed franchise, Rockstar’s effort seems to have been developed in parallel to the rest of the genre. Ubisoft inspired open world games are largely be defined by a few mechanics, such as expanding the map via some sort of tower, repetitious side missions that fill out the map, and the heavy use of fast travel. While these systems aren’t all inherently bad, RDR2‘s rejection of these trends is refreshing.

Instead of incentivizing players to make a beeline to the next map-expanding waypoint or repeated side activity, the game’s Stranger missions must be found naturally through exploration. While roaming the wilds, you can hunt a wide variety of game and catch fish, offering a consistently entertaining way to make money. Random small interactions can occur with passers-by, resulting in the gain or loss of Morality, a metric which tracks your deeds. But beyond these gameplay hooks, a great deal of this world’s allure comes from the fact that this envisioning of the Old West is nothing short of one of the most aesthetically impressive undertakings ever in a video game.

The world functions as a microcosm of different regions of America, with swampy bayous, desolate plains, verdant forests, and snowy mountains brought to life via a mostly realistic yet stylized aesthetic. Here nature often looks like an idealized version of the real thing, seemingly inspired by the Hudson River School movement’s Romantic-styled paintings. This all comes together to create a space that feels as immaculately designed as it is large, a combination that is traditionally almost always impossible due to the absurd degree of time and money that is necessary to make this so. I had many instances where I would explore this space and live like an outsdoorsman, not for the sake of gaining XP or improving a completion percentage, but due to the incredible degree of craft that has gone into this envisioning of natural Americana.

It also helps that Rockstar’s latest boasts their strongest writing by a mile. The recent GTA games have largely been satirical farces, which is likely a creative decision at least partially designed take the edge off of all the mass murder. While those titles certainly had their moments, their plots often fit together like a loosely related mishmash of character interactions, thinly tied together with a main plot that was too bogged down in satire to actually be emotionally affecting. While the original Red Dead Redemption had a strong ending and an interesting dramatic through-line, its pacing was completely derailed by a nonstop barrage of narrative fetch quests. Although the main plot of RDR 2 is similarly labyrinthine, as it still adheres to the same basic structure of the studio’s previous games, the difference here is that it feels as though this complements the slow-motion dissolution of this band of outlaws.

The story follows Dutch’s band of outlaws in the final days of the wild west, functioning as a prequel to events of the previous title. Much like in that game, the story missions often instill the feeling of constantly grasping at straws, with things rarely working out as intended as one story mission spirals into the next. However, instead of feeling like padding to divert you from your main goal, here when the plot threads suddenly take hard unexpected turns, it feels as though this matches the increasingly desperate situation that these characters find themselves in. There is a grim inevitability to the proceedings due to the game’s nature as a prequel, which goes nicely with the more self-serious tone. While I have misgivings towards the satirical edge of previous Rockstar games, I did enjoy the ridiculousness of many characters they had crafted in the past. Luckily, here there is a split between the grave main story, and goofy, irreverent side content of the Stranger missions, giving opportunity for some optional satire in between the heavier proceedings.

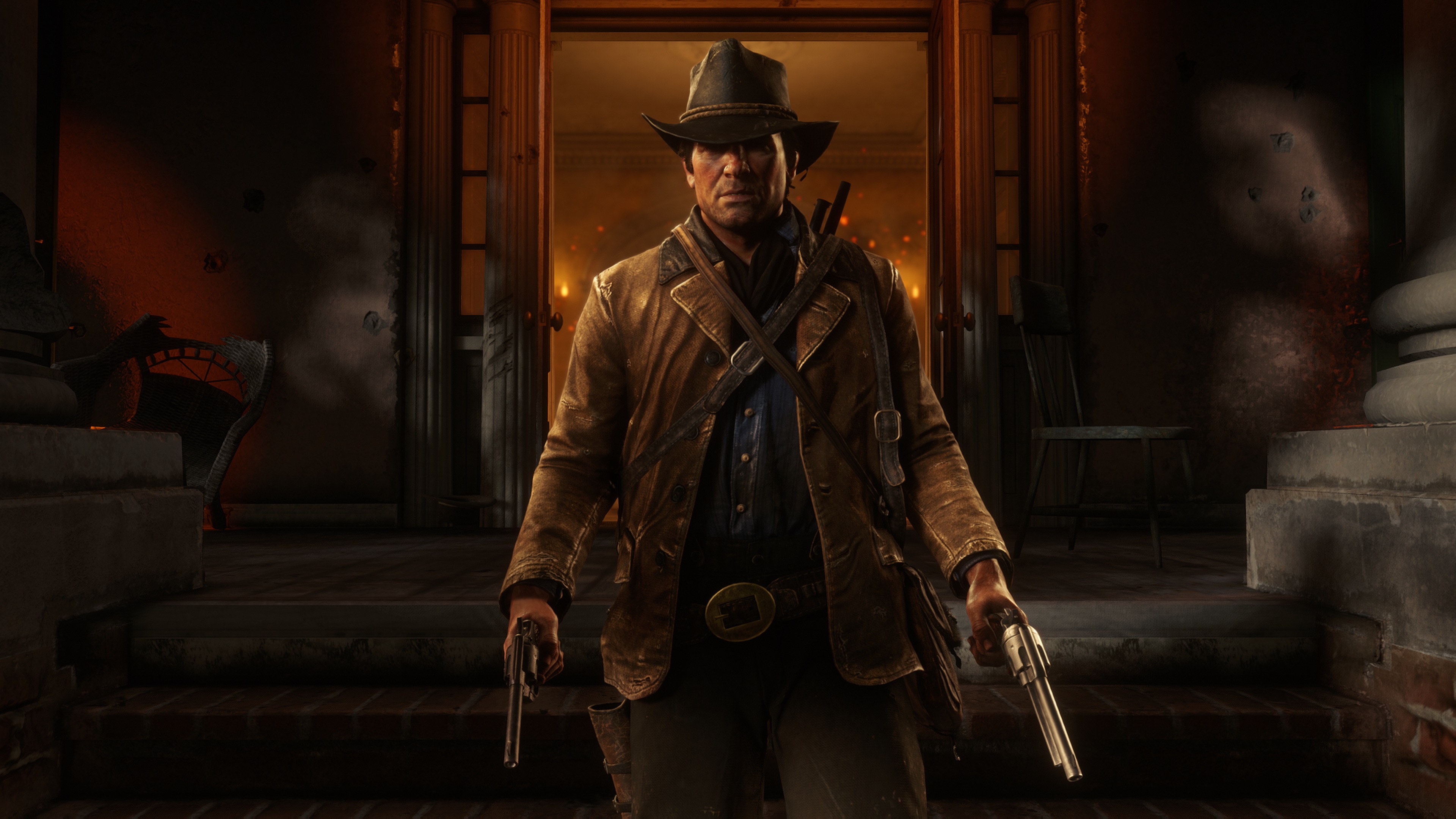

The beating heart of this story is Arthur Morgan, an initially gruff enforcer type who functions as the gang’s workhorse. Although his endless jabs at his compatriots and seemingly threatening demeanor make him an offputting protagonist at first, his true nature slowly comes to the forefront. As we spend more time with him his tough guy persona melts away, revealing a complex individual who has severe misgivings about the activity of Dutch’s gang. This comes across in his interactions with fellow gang members, in subtle gestures, and especially through his entries in his journal, in which he wonders if he can find some semblance of goodness in a life that has gotten away from him.

The inclusion of this journal is a fairly brilliant stroke, giving inferences into the mind of our protagonist in a naturalistic fashion. It makes it clear that much of his badass cowboy act is a bunch of chuff, concealing his many doubts. There are also genius little inclusions such as a newspaper clipping that Arthur keeps near his bed that gives insight into his bygone idealism. The clipping recounts one of his first robberies with Dutch, in which the gang pulled a Robin Hood and gave away all their loot to the poor. The main story builds on all of these incidental details, and the final few chapters do an excellent job of giving this character the redemption he deserves.

The rest of the cast is similarly well-developed, in large part due to the truly vibrant camp sites that serve as your frequently moving home base. Back at camp you can interact with every member of the gang, and overhear conversations between your compatriots. The amount of dialogue and voice work here is astounding, your crew constantly commenting on recent events, having causal conversations, or breaking out into song. I spent many hours just roaming my base, getting to know my fellow gang members better.

There’s Sadie Adler, the widow turned gunslinger whose wit and ferocity make her an imminently likable heroine. Lenny, the new kid, is introduced in a hilarious mission that depicts the experience of getting absolutely housed at a saloon. Your old friend and role model Hosea is an anchor for the group, a charismatic conman. We get to see the original game’s protagonist John Marston, whose brotherly bond with Arthur naturally grows over the course of the plot. The diversity of this band of misfits is not only pleasantly inclusive, it also allows for the presentation of many unique viewpoints. We have Charles, the son of a Native American and African American, whose mixed heritage has pushed him to the fringes of society. Lenny and Tilly point out their concerns during the gang’s stay in the South. The lack of discrimination among Dutch’s band also operates as one of the many little beacons of morality that are a consistent undercurrent among all of the misdeeds, a byproduct of their leader’s once apparent sense of morality.

The key differentiating factor between this game and Rockstar’s previous titles is that despite all of the criminal activity and gunslinging, there is a core earnestness to the writing that puts the wry humor of their previous games to shame. Even in the zanier side stories, the vast majority of characters don’t exist just to be mocked or parodied, they are meant to be empathized with in some way, or to convey the game’s core themes. Although I admit that frequent shootouts result in cartoonish body counts, the core theme here is one of redemption. Arthur is a man who has done bad things, but his internal struggle with these actions is palpable. His jabs and sometimes brutal demeanor hide his actual desires and regrets. As the plot barrels towards its conclusion, these regrets are articulated in a believable fashion that makes Arthur’s development feel earned.

Another core theme is the subversion of the genre’s glorification of the old west’s greater freedom from governance. While Westerns generally aggrandize the bygone libertarianism of a lawless society, RDR 2 feels somewhat conflicted over this notion. On the one hand, the Pinkertons that pursue you are presented as somewhat villainous, and the sociopathic industrialist who pays them, Laviticus Cornwall, is similarly vilified. But despite the symbols of the law being thoroughly unlikable, Dutch’s vague anarchic tendencies are presented as facile and ultimately unjustified, your criminal acts stemming far more from desperation than justice. Arthur wrestles with the fact that his mentor figure is both wrong, and largely unhinged, never diluting himself into believing his actions are anything but immoral.

This functions as something of a rejection of the deification of gunslingers in traditional westerns, and despite the fact that many of your compatriots are likable characters, it never feels as though their criminal actions are entirely warranted. The result of the changing times is more often presented as tragic due to the encroaching destruction of the environment more than anything else. By presenting this beautiful portrait of America’s natural grandeur, the introduction of the garish, smog-filled city of Saint Denis works as a wordless counterpoint to the prospect of urbanization. The previously described immaculately designed world makes the case for transcendentalism as succinctly as any piece of fiction could, America’s natural beauty presented as a relic of the past.

Overall, Rockstar’s latest is a fascinatingly messy game, its gorgeous world, well-written characters, and dense central plot, contrasting with its outdated gun-play and laborious elements. The soundtrack combines with its lush visuals to provide a highly coherent aesthetic style, creating a truly immersive depiction of the West. Well-written dialogue is amplified by stellar voice acting, and its narrative is genuinely affecting. But, all the while the protagonist controls like a tank, and the overlong gunfights bog down story missions. In short, Red Dead Redemption 2 is a flawed but thoroughly ambitious creation, one that capitalizes on its strengths in a fashion that ultimately allows it to transcend its numerous issues. It may not be a snappy shooter, but Rockstar’s magnum opus functions as an excellent showcase for the potential of open world games.