Similar to how the ‘found footage’ concept cultivated a popular sub-genre of early 21st century horror cinema, the 2010s have likewise witnessed the birth of a new film-making technique; one far more societally and technologically relevant to our digital age. Dubbed ‘Screenlife movies’ by Searching producer Timur Bekmambetov, these films are presented strictly from the point of view of computer and/or smartphone screens.

The technique has been used several times already; a 2013 Canadian student short-film titled Noah about a teenager breaking up with his girlfriend being one of its earliest uses, the social media-themed horror Unfriended (also produced by Bekmambetov) brought the concept to a mainstream audience in 2014, and earlier this year Profile (directed by Bekmambetov) applied the method to a mystery/thriller format – even the beloved American sitcom Modern Family made excellent comical use of the technique in the fantastic 2015 episode “Connection Lost”. But, just as the 1999 independent horror The Blair Witch Project popularised the found footage method, it could be argued that Searching has just elevated the concept of ‘Screenlife movies’ to an entirely new sub-genre in itself.

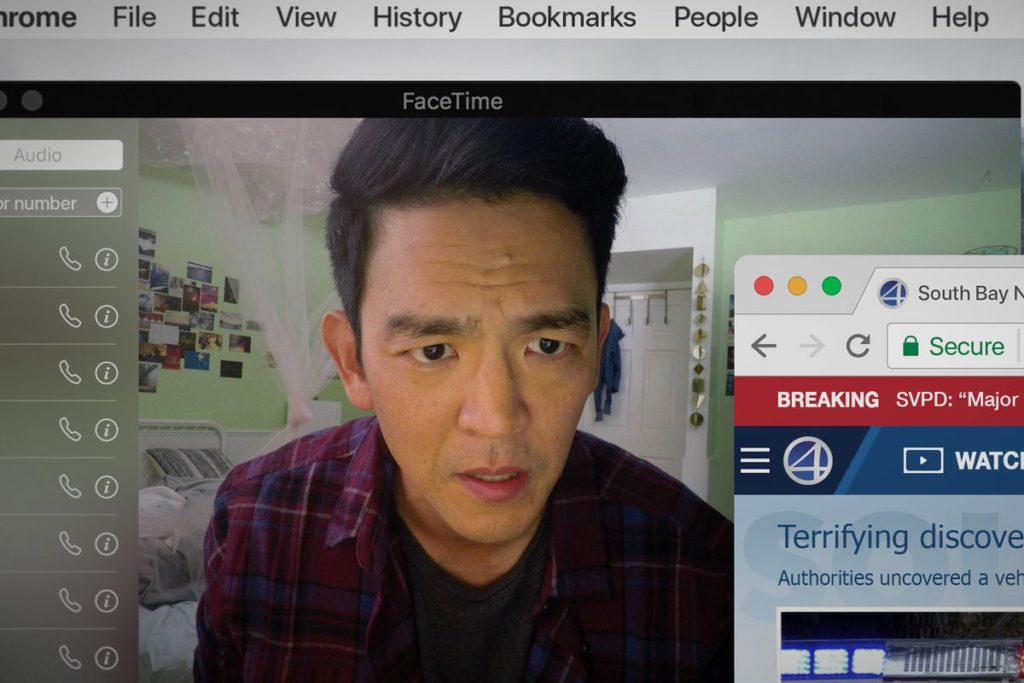

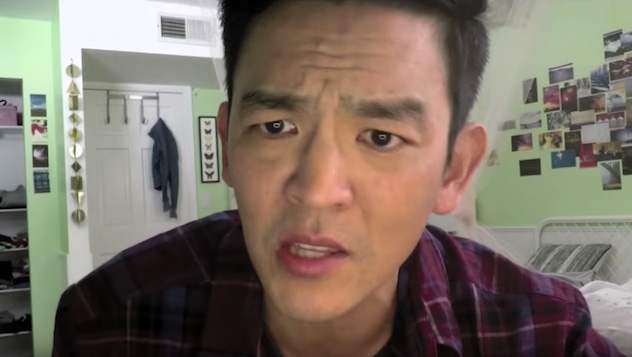

Searching follows David Kim – in a mesmerising performance by John Cho (Star Trek, American Pie) – as he tries to find out what happened to his missing daughter Margot (Michelle La). David goes about this primarily by checking her social media activity, FaceTiming with lead detective Rosemary Vick (a terrific Debra Messing) and, well, making Excel spreadsheets detailing who last saw her and when – all whilst the viewer sits watching though the little camera on whichever laptop or smartphone David happens to be using.

When pitched as a premise, it’s hard to think of the Screenlife concept as anything more than a gimmick, but with Searching, first-time director Aneesh Chaganty effectively cements the idea as an intelligent and extremely powerful narrative technique. By viewing events exclusively from such an unconventional perspective – one simultaneously both detached from and engaged with the action – the viewer is granted a unique understanding of David Kim’s state of mind and state of living.

The concept is masterfully introduced to the audience when, at the start of the film, we are shown a heart-wrenching montage of old videos and photos depicting the Kim family’s battle with cancer (seemingly throwing its hat in the ring with Up for the title of ‘Fastest Film to Make Viewers Cry’). From there we are given a secretive, almost voyeuristic, view of how widowed husband David Kim now proceeds to live what life he feels he has left – noticeably removed from all meaningful social interaction; avoiding most social outings and speaking to friends and family almost entirely via instant message or video call. This new impersonal and inattentive form of living is ensuingly thrown in his face when he discovers that, based on accounts from Margot’s school friends and her own online activity, David realises he no longer truly ‘knows’ his own daugter.

While the Screenlife concept certainly lends itself effectively to the ‘thriller’ side of the movie – creating a heightened, authentic tension by convincing viewers they are closer to the action than normal – it is how the concept lends itself to the ‘drama’ side of the movie that stands as truly remarkable; creating a heightened, authentic sense of empathy in viewers. Witnessing first hand what David Kim types, searches and views ensures we are able to understand exactly what’s on his mind, what he truly cares about. Seeing familiar brands and services mixed up in the action further ensures events appear both uniquely believable and relatable. Of course, Cho’s masterclass of a performance (one likely made unimaginably more difficult to produce by having to spend the majority of the time looking just to the right of the camera) also helps immeasurably in this regard.

Unfortunately the movie is by no means ‘flawless’ and does in fact itself fall prey to the limitations embedded within its original concept. While the inherent appeal of the Screenlife technique lies in its aggressive engagement of the viewer by placing them literally directly in front of the action, occasionally Searching feels the need to ‘zoom out’ somewhat and use other ‘screen formats’ – such as news footage – to more clearly explain certain events. Unfortunately it is in these instances when the ‘gimmick’ side of the technique begins to creep back into view; where the mode of storytelling starts to bend to meet the needs of the story (after all, some things are just kind of hard to explain using a computer screen).

Also, while the screenplay is brilliant and stands to construct a solid thriller in its own right, its second half nevertheless feels a little superfluous; packed with perhaps one too many twists that, while certainly shocking and entertaining, serve to detract somewhat from the story’s commendably principled focus on raw authenticity.

All things considered, however, Searching is a truly magnificent piece of film-making; one driven not only by an intelligent and imaginative brain, but also by an understanding and empathetic heart. Come for the thrills, stay for the unnerving era-relevant chills.