Ah Quick-Time Events…. Perhaps the ‘house spiders’ of universal gaming: annoying, not particularly nice to look at and it feels like they’re just everywhere; but if we try to suppress our instinctive state of repulsion for just a second, one could make the argument that these pesky creatures can actually be quite useful. That’s right, just as spiders help to clear our households of pestilent insects, QTE’s might also be seen to possess benefits that may not be immediately obvious to the eye. Intrusive and irritating they may be to some but button prompts and contextual actions, when used in the right ways, serve as valuable tools in maintaining a game’s level of interactivity, and through that the player’s state of immersion. The problem is there are a whole bucket-load of ‘wrong’ ways to use such actions that can instead cause the player’s state of immersion to collapse in on itself, like an undercooked soufflé.

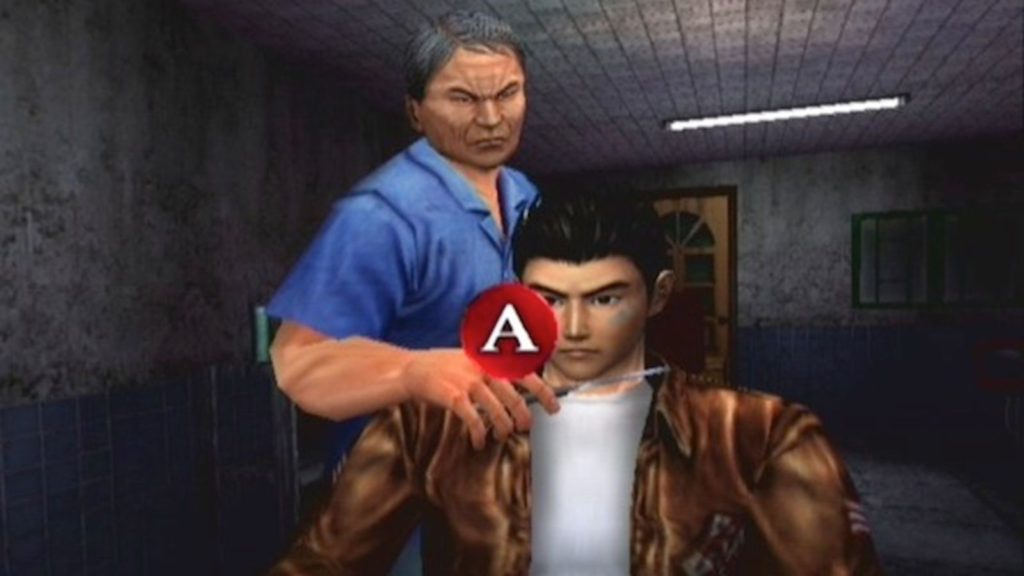

As is probably common knowledge by now, we have Yu Suzuki and Shenmue to thank (or blame, depending on your standing) for the current popularity of ‘Quick-Time Events’ (or ‘Quick Timer Events’ as Suzuki originally coined them). Sega Am2’s Dreamcast classic was wholly dedicated to offering players a higher level of narrative interactivity, and one of the ways they attempted to provide this was by affording players a unique, albeit entirely basic, control over certain action-oriented cinematics.

Today, QTE’s are used to convince players they have similar interactive influence over even the most elaborate or unconventional animations – whether its ‘Mash O to beat this awesome boss to a bloody pulp’, or ‘Press F to casually pay your respects at this funeral’.

So let’s explore some of the reasons QTE’s are employed in games today; whilst also looking at both the games that get it ‘right’, and those that get it oh so ‘wrong‘…

Reason #1: Storytelling – Player agency comes cheap

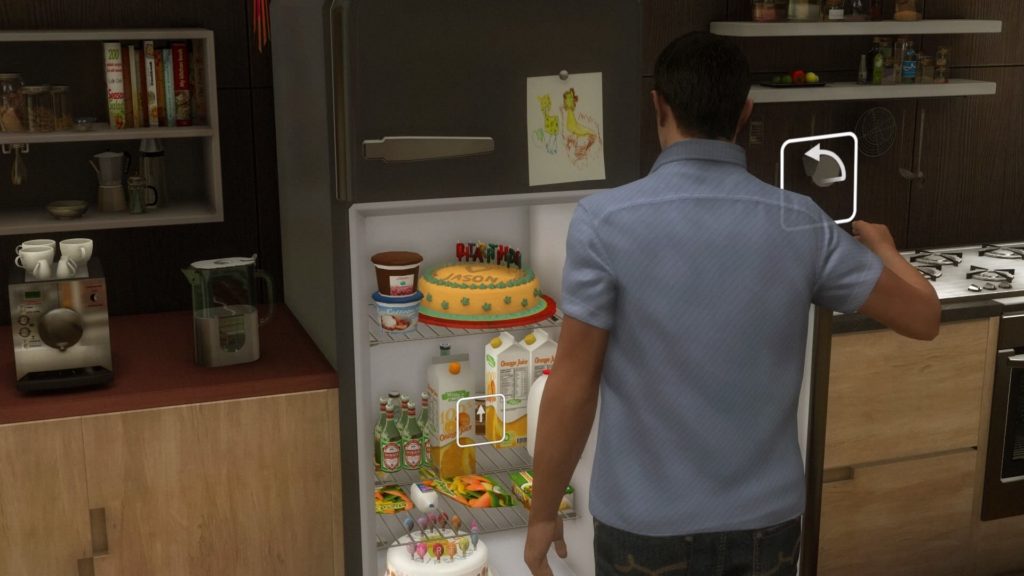

One of the more obvious functions QTE’s possess is the ability to grant players a perceptible level of influence over a game’s narrative. Quantic Dream and Telltale, for instance, use quick-time events to help create a unique cinematic experience; with their games using button-prompts to denote important narrative decisions or dialogue options. Similar prompts are likewise assigned to a range of contextual movements – whether its punching a bad-guy in the face or pouring milk into a bowl of Cornflakes, the character likely won’t be able to do most things without some sort of player-input. And while eating cereal may not be the most exciting aspect of any game-story (at least of any good game-story), providing this volume of interactivity ensures the player remains continuously connected to the action and the characters. In this way, narrative immersion is kept perpetually intact.

That being said, an over-reliance on QTE’s can easily serve to hinder narrative immersion, particularly when the failure of said QTE’s doesn’t have any sort of tangible impact on events. Check out this rather hilarious Heavy Rain clip and you can see what we mean:

Of course, considering gameplay in these sorts of titles fundamentally wouldn’t exist without QTE’s, the positive side of this argument seems somewhat moot. So what about a game that doesn’t rely on quick-time events for storytelling, but instead uses them to enhance it? Enter Naughty Dog…

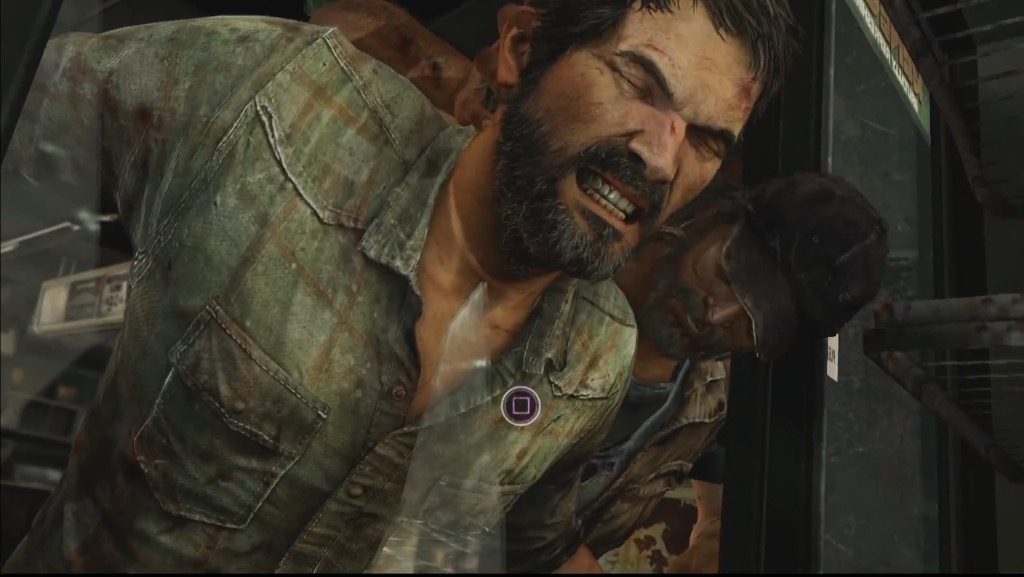

Incorporating an absorbing and emotional story into a game is an incredibly difficult task for a developer. It’s not enough to have an intriguing premise, or an exciting plot, or even a great cast of characters; what’s most important is how precisely the story is told. To tell The Last of Us‘ phenomenal story, Naughty Dog used a crucial combination of motion-capped cut-scenes and in-game cinematics. And during many of these in-game cinematics, animations are triggered manually by the player using, you guessed it, ‘quick-time events’. Players would find themselves mashing a button to keep a Clicker from making a tasty snack of Joel’s face, or hammering another as Joel manically grabs for his pistol while a Hunter attempts to drown him.

Naughty Dog here uses QTE’s strategically: by simulating Joel’s panicked struggles more physically and authentically, they are thereby able to effectively maintain the action’s visceral momentum and further secure the player’s perceived connection to the protagonists and their story.

As we all well know, however, not all developers succeed in incorporating QTE’s quite so neatly into their games. Some games even employ them so haphazardly that they end up completely contradicting the very reason they’re used. Take Crystal Dynamics’ otherwise fantastic Tomb Raider reboot, for example. For Lara Croft’s updated outing, the developer committed to telling a considerably more gritty, personal and overtly cinematic origin story. While they certainly succeeded in doing this, one factor that served to dramatically hinder the experience was the reckless inclusion of quick-time events.

Crystal’s former Tomb Raider games had used QTE’s to break up gameplay segments with some ridiculous John Woo-style action set pieces. While pointless and irritating, they were relatively infrequent and did at least offer some comically over-the-top death animations (Lara could be eaten by a Velociraptor, gobbled-up by a T-Rex or even eaten by a Velicoraptor that is then itself gobbled-up by a T-Rex).

With the reboot, however, QTE’s were inserted more directly into gameplay segments in an effort to make the game more ‘cinematic’. Well, put simply: it didn’t work. This was primarily due to the mechanics of the QTE’s themselves which, quite extraordinarily, actually managed to make the process of ‘pressing a button’ overtly complicated.

When a creepy man grabs Lara’s ankle, rather than settling for the traditional ‘tap this button to not die’ system, the game instead orders the player to declare war on the left analogue-stick and then participate in some boring minigame where you have to press the ‘interact’ button at precisely the right time to succeed. Not only did this completely break the flow of both the gameplay and the narrative – I mean I’m pretty sure Lara wouldn’t pause to carefully ‘time’ a panicked boot-to-the-face – the QTE itself was also made infuriatingly hard by the fact that you weren’t told what button you had to press until about 2 seconds before you failed the interaction completely, and fatally.

This is to say nothing of the hell PC players went through, where these 2 seconds were mostly spent trying to remember which of the 59 buttons on their keyboard happened to have been assigned to the ‘big red exclamation point’ icon.

Rather than making the game ‘cinematic’ and ‘immersive’, the movie-style storytelling was intermittently broken with the game repeatedly showing us sadistic game-over clips that featured Lara getting crushed by a boulder, shot it in the face or impaled on a giant tree branch.

And of course we can’t rant about QTE’s potential negative effects on storytelling without bringing up a couple of meme-tastic classics:

https://youtu.be/hRR-ssPdmWY

While ‘press x to Jason’ may understandably have seemed a good way to encourage the player to empathise with Ethan’s panicked state, allowing the player to cycle through the 3 or 4 recorded variations of the word as many times as they please throughout the entire 3-minute sequence was just asking for trouble…

And it’s hard not to actually suspect Sledgehammer Games of purposefully inventing a meme with this completely nonsensical inclusion of a quick-time event into an emotional storymoment…

Reason #2: Challenge – Because cut-scenes are just too easy

Yes, some developers often decide to throw QTE’s into their games with the simple intention of keeping players on their toes. Instead of just being a spectator to a protagonist’s awesomeness, the player is forced to play a part in certain action sequences – for better or worse. The ‘hack-and-slash’ genre, in particular, is somewhat notorious for its habitual use of button prompts in this respect: after tasking us with dodging, slicing and dicing our way to victory against an especially powerful enemy, many developers requested we earn our final, satisfyingly gruesome coup-de-grâce by tethering it to a relatively simple quick-time-event. God of War of course represents one of the most famous examples of this dynamic.

At the risk of having digital tomatoes pelted at my head, I must declare I always rather appreciated this system; rather than each of my battles serving as one long and elaborate set-up for Kratos to deliver the ultimately satisfying deathblow; it felt somewhat gratifying to at least be included in the final execution as well. Even the recently released God of War (2018) made use of QTE’s, although admittedly far more sparingly than its predecessors.

That being said, one franchise that consistently manages to offer players a frantic and stimulating experience without so much as a whiff of an interactive cutscene, is Devil May Cry. Capcom’s dramatically elaborate and wildly stylish DMC boss battles are themselves so intrinsically entertaining – not to mention unapologetically challenging – that the inclusion of QTE’s is not only fundamentally unnecessary but would actually serve to irreversibly taint the ‘purity’ of the experience as a whole.

In light of the above notion, however, it may not be entirely ‘fair’ to compare these two games; after all they each seek to offer players very different playing experiences. Whether you prefer GOW‘s ‘challenging yet fluid and cinematic’ combat or DMC‘s ‘relentlessly taxing, skill-based mayhem’ comes purely down to personal opinion; with the existence or non-existence of ‘quick-time events’ in these games likely only factoring in as a basic point-of-reference to argue such an opinion (as in you don’t prefer GOW because it has QTE’s, but rather are more tolerant of QTE’s because you prefer GOW‘s style of gameplay – and vice versa).

Technically this generous acceptance of such a basic and condescending mechanic might easily be perceived as naïve, but when a cinematic game presents the player with a choice between ‘no’ interaction and ‘some’ interaction I always felt the latter seemed naturally more appealing – provided it did not interfere with the general experience in any way.

Reason #3: Physical Effect – If your character is out of breath, you should be too

Another potential effect QTE’s can contribute to a game is to physically manipulate a player into feeling more personally connected to the action. In situations where an on-screen character is performing an especially exhausting, intense and/or narratively vital action, some developers feel simulating such a feeling in the player will help more effectively immerse them in the game’s events. Granted this seems suspiciously similar to the earlier explanation of how quick-time events are employed to strengthen storytelling; but whereas a ‘storytelling’ QTE is designed to allow the player to influence on-screen events, a ‘physical-effect’ QTE conversely is designed to have an influence on you.

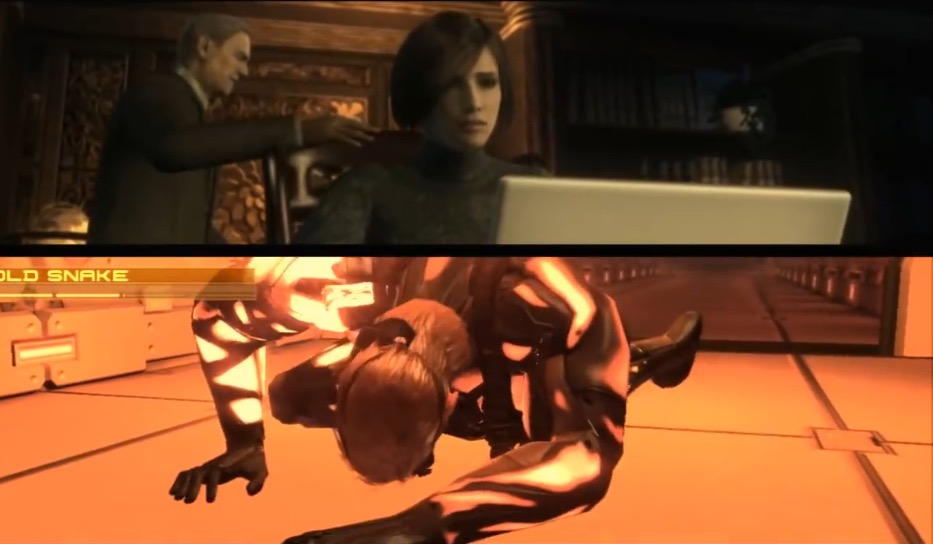

Metal Gear Solid IV‘s climactic ‘microwave hallway’ sequence undoubtedly stands as the definitive example of this narrative technique. Towards the very end of the game, Old Snake must crawl through a long corridor perpetuated with intense microwaves. The screen is split horizontally; with the bottom half showing Snake determinedly powering on as his bodysuit begins to burst and cripple from the intense heat and pressure, while at the top plays a cutscene featuring all the characters that are counting on Snake – and the player – to make it to the end. It truly is a tremendously intense and emotionally powerful scene.

However, one of the defining features of the sequence is that it is effectively powered by one long quick-time event. As Snake’s health bar is steadily depleting, the player must continuously press the triangle button to keep him pressing onwards. Considering the scene itself is rather a long one, this QTE makes for a fairly tiring task for the player. While this may sound considerably annoying on paper, in practice the mechanic makes for an incredibly engaging experience. Snake’s seemingly endless struggle is expressed to the player in an emphatically physical fashion, which resultingly serves to intensify the emotional impact surrounding it.

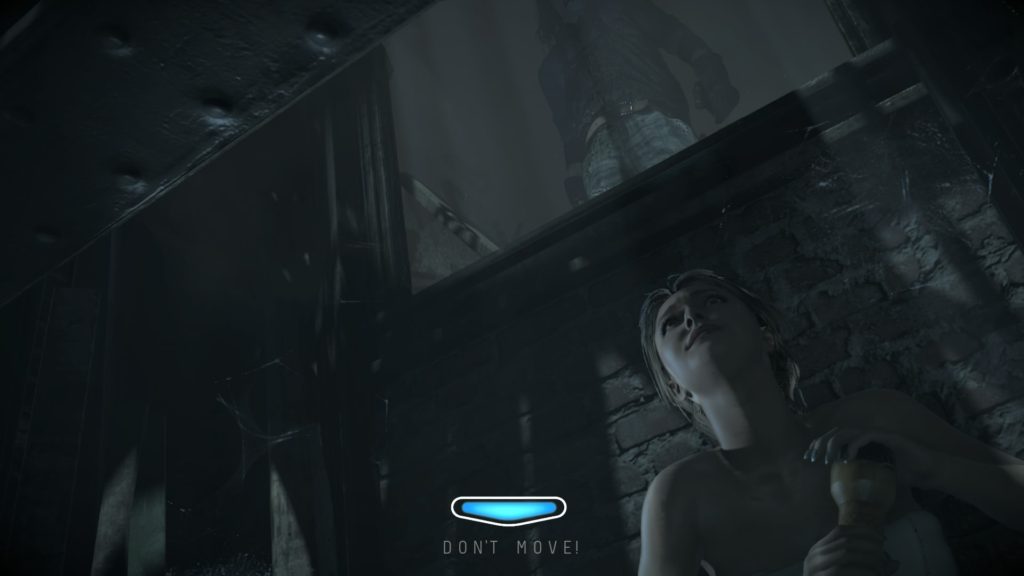

Another, somewhat more basic, example of this type of physical QTE can also be found in Supermassive Games’ cinematic-horror adventure Until Dawn. Like similar drama-centric titles, the game makes heavy use of button prompts for both its story and action sequences, but one of the more inventive QTE’s it incorporates is the ‘Don’t Move’ instruction. During especially tense moments, such as when a character is hiding from an approaching enemy, a little outline of the PS4’s controller light will appear at the bottom of the screen telling the player to keep the joypad as still as they possibly can. At that point, the dualshock gyroscope technology kicks in and if too many slight tilts are detected the player will fail the sequence.

While at first the QTE feels a difficult one to fail, as the game progresses, and player tension rises, it becomes increasingly harder to maintain your composure while your heart feels like it’s beating in your throat. Couple this with the knowledge that any one of the eight character you play as can die at any time, and this smart quick-time event can actually make for some pretty exciting, adrenaline-fuelled moments.

Of course, sometimes the intention of using a QTE to exert a physical influence over players doesn’t always have a positive effect on the narrative experience. One of Quantic Dream’s earlier titles, Fahrenheit/Indigo Prophecy, stands as a particularly infuriating example of this. While Heavy Rain made use of the face buttons for the majority of its quick-time events, Quantic’s earlier QTE-system focused predominantly on the analogue sticks. Unlike other games that try to trick the player into thinking the button they are pressing during a particular prompt directly corresponds to a visible action on-screen, Fahrenheit just goes mental. Two colour wheels appear in the middle of the screen, each split into 4 coloured segments that light up to inform the player of which direction they must flick each stick. If you’ve ever wondered what it would be like to play Guitar Hero on a regular controller I think playing David Cage’s unusual supernatural thriller would give you some idea.

Although the intention, like MGS, is to make the player work hard during intense sequences, when your frantically flicking analogue sticks every which way just so a character can make a simple investigative observation it can be more than a little narratively distracting.

Worse still are the ‘physical effort’ QTE’s that have you alternately mashing the shoulder buttons like a complete maniac:

Reason #4: Set Pieces – Press ‘x’ to make jaw drop

As well as offering additional levels of interactivity, quick-time events are a good way to break up traditional gameplay with exciting set-piece events and animations. Whether its jumping onto the moving cargo plane in Uncharted 3 or using a throwing knife to save Captain Price from being beaten to death in Modern Warfare 2; sometimes a little QTE sequence can be a great way to make the player look and feel ‘cool’.

One franchise in particular that quickly discovered the aesthetic potential of QTE’s is Kingdom Hearts. A new mechanic for the series’ second outing, labelled ‘reaction commands’, allowed players to trigger unique and stylish animations in the middle of combat by pressing the triangle button when prompted. Used especially frequently during boss fights, the system was a neat way of keeping encounters fresh and entertaining.

Many games, in fact, use QTE’s to add a cinematic element to boss fights. Leon’s famously elaborate knife-fight against Krauser in Resident Evil 4 stands as one example, as does fencing with Rafe in Uncharted 4‘s wonderfully climactic finale.

One game, however, that took the notion a little too far was Halo 4. Not only did the game’s final boss fight consist of a short and inexcusably boring set-piece, the QTE used to activate it was horrendously easy to boot.

In this instance, using a quick-time event to create a ‘cinematic’ set-piece finale effectively robbed the game of its credibility and subsequently destroyed its narrative momentum. Fortunately the final cutscenes were intriguing and emotional enough for the story to regain its feet, but 343 Industries preposterous idea of a ‘final boss fight’ nevertheless remains impossible to forget, let alone forgive.

Reason #5: For Comedic Purposes – Because sometimes, they’re just bleedin’ hilarious…

While perhaps not quite as significant as their other uses, occasionally quick-time events are just a good way of giving the player a bit of a laugh.

For instance, while QTE’s in certain Telltale games tend to feel a little dull or uninspired, one of the games that makes great use of them is 2014’s Tales From the Borderlands. In previous entries, many of the QTE’s felt out of place – even unwelcome – and would tend to interrupt a lot of the fast-paced action, thereby sapping its momentum. In TFTB, however, the ‘stop-start’ feel intermittent QTE’s created in each scene seemed to work perfectly with the game’s comedic style and timing.

And of course who can forget the joy of slapping Wolverine in the face for 2 straight minutes in Deadpool: The Game?

And there we have it, 5 reasons quick-time events can arguably be quite useful at times. Yes alright they can still be sort of annoying – particularly when they’re implemented so lazily – but maybe every now and then we can give at least some developers a break.

And to the more stubborn QTE-haters out there who think we’re talking complete rubbish: press X…