What essentially is a ‘narrative’? Is it a story? An experience? A journey of emotion? In short: yes. More than this however, it is a reality. Watching a film or a TV show is a rather unusual experience when you think about it. On the one hand you know these characters aren’t real, these people are just pretending. That furry little creature prodding Princess Leia is really just Warwick Davis in a bear suit. But even with this notion of common sense firmly embedded in one’s mind it doesn’t stop us from allowing ourselves, just for a couple of hours, the freedom to let go. We make this subtle but altogether conscious decision to forget logic, deny what’s ‘real’ and immerse ourselves in this new world. Whether we feel we actually enjoyed our visit there once those hours are up is obviously another matter.

We value films primarily because they provide us with a window into these new worlds, these new ‘realities’. But what is the function of a window? To look through. To allow you to see something whilst remaining crucially separate from it. Sure you can see some pretty amazing stuff, but nonetheless are left twiddling your thumbs while doing so. But where movies give you popcorn, games give you a controller, and suddenly ‘twiddling your thumbs’ becomes an integral part of the narrative experience.

So let us take some time to celebrate a few of those developers that work so tirelessly to provide us with the best kind of narrative experience: an interactive one.

The trials of a ‘narrative designer’

It’s important first to acknowledge just how hard game-writers (or ‘narrative designers’) have it. Even if they are wholly committed to telling a uniquely poignant, detailed and intricately structured story, it remains practically inevitable their vision will conflict with how a ‘game’ is constructed on a fundamental level.

For one thing, regardless of how the developer decides to tell the story, the game itself will consist primarily of ‘gameplay’ – moving/shooting/climbing/running over innocent pedestrians etc. This means the overall ‘story’ will exist generally as context in the player’s mind – the ‘goal’ or ‘goals’ they, as the character, are trying to achieve. The player cares just as much, if not more, about what sorts of things the game allows them to do, than how the story reveals itself. To put it simply: we want games to be ‘fun’! Characters, plots, game-worlds remain important to us – we like to care about what we’re doing – but we also want to feel cool or smart or powerful while we do it, and this is where the story struggles for attention. We’re sat comfortably in the driver’s seat, Mr. Developer is riding shotgun showing us how to work the car and all the cool stuff we’ve got in it whilst pointing out those pretty views, but too often poor Mr. Writer is stuck in the back tapping us on the shoulder every now and then to tell us to “take a left up here” or a “right down there”. Worse still he might end up locked in the boot after the player’s just decided “Alright, I think I’ll take it from here.”

Another issue writers have to contend with is present in the fact that the player isn’t just watching the main character do his/her thing, they are controlling them. In a sense, they ‘are’ them. Narrative immersion demands that the player’s consciousness, mentality and even personality must naturally synchronise with the character. Only once the characters’ goals have become our ‘goals’ can we feel fully engaged. This is a supremely difficult thing to achieve for a writer and developer and if it fails they often risk ‘ludonarrative dissonance’ – the term given to the situation in which a player is denied the option of doing something they want to do, or worse made to do something they actively don’t want to do. All illusions of control are shattered; where once the player felt they were aiding the story, now they’re simply abetting it.

‘Cinematic storytelling’ taken literally – Quantic Dream

One of the more blatant, unapologetic narrative dynamics is the straightforward ‘interactive-drama’. Telltale, for instance have found enormous success in their episodic, narrative-driven formula. Nevertheless, as fun and entertaining as each of their titles serve to be, this success could be attributed just as strongly to the developer’s penchant for adapting popular film/TV franchises for their games than to the mechanics of the games themselves. A developer that strives to advocate this cinematic dynamic without the safety net of nostalgic pop-culture references, however, is Quantic Dream. There can be no denying that Quantic has settled on a very innovative way of combining ‘narrative’ and ‘gameplay’, although the developer’s ‘story-first’ approach tends to polarise gamers.

A notable dependence on quick-time-events, for instance, is often cited as one of their games’ more controversial features. As necessary as QTEs are to attain the desired levels of interactivity in these types of games, the precise way in which they are integrated into gameplay serves as practically the sole difference between ‘satisfyingly interactive’ and “oh my God, if you tell me to press ‘x’ one more time I’m going to eject the game-disc and feed it to my neighbour’s bulldog…”

Detroit: Become Human, however, could hopefully win over more than a few sceptics with its determination to infuse more ‘game’ into the scenario. If you’re inclined to learn more about how Quantic Dream have bridged the gap between video games and Hollywood, our full history of the developer may pique your interest.

The open-world narrative, moving at the player’s pace – CD Projekt RED

It’s relatively simple to structure a linear narrative around a game that follows a linear level-structure, but not so easy to do in a game that allows the player to effectively go where they want, when they want. Open-world games, these days, tend to come toting some intimidatingly expansive landscapes; each luring us into spending often embarrassing amounts of time exploring every inch of them. Incorporating a ‘linear’ narrative into this kind of exploration-based dynamic often serves to be a very tricky undertaking, as the traditionally rapid and intense pace of many action/adventure stories actively contradicts the loose and leisurely pace of free-roam gameplay. When the match works, however, it can make for an incredibly immersive and rewarding playing-experience.

Take The Witcher 3, for example. CD Projekt RED’s critically acclaimed title, in case you somehow didn’t know already, is bloody brilliant. It offers up an enormous and breathtakingly detailed open-world, a richly fascinating cast of characters and a varied, intuitive combat-system. What it also offers, however, is the chance to lose oneself in a wonderfully engrossing and emotionally riveting narrative. As with many games of this ilk, the narrative moves purely at the player’s pace with missions manifesting themselves more as a glamoured-up ‘to-do-list’. The player can follow each objective consecutively, or abandon the main campaign entirely to venture out and start ticking off all those ‘points of interest’ that make each map look like it’s contracted an alarming case of question mark-acne.

Of course, there are countless games that utilise this same dynamic – breaking up the main narrative with side-quests. So what sets The Witcher apart then? That would be the inherent quality and effort dedicated to the side-quests themselves; with a random mission you found while casually passing through a village often ending up being just as fun and emotional as the last story quest you did. What the game narrative lacks in upbeat, adrenaline-heavy pacing it more than makes up for in its phenomenal sense of immersion, spearheaded by a heightened level of player agency and remarkably absorbing side-quests.

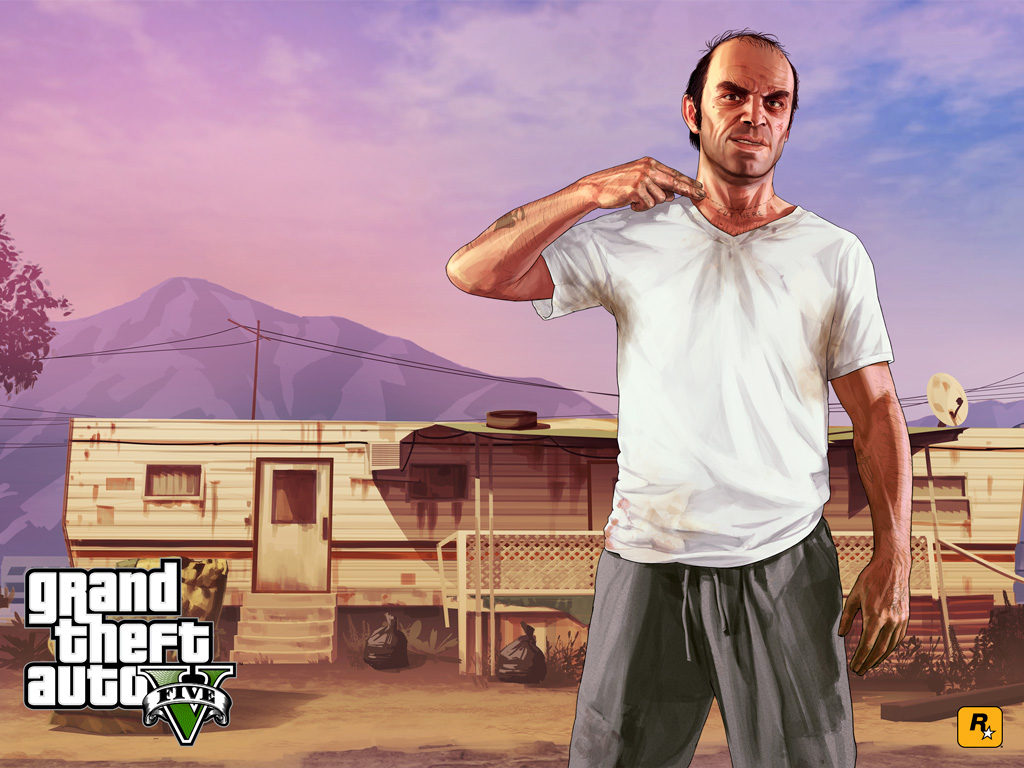

The [il]logic of narrative in a ‘Sandbox’ – Rockstar Games

Unique challenges emerge for developers looking to build a narrative into an open-world game, but these challenges intensify further when the setting is intended as a ‘sandbox’. Where an open-world encourages exploration, a sandbox encourages experimentation. The developer explains the game’s mechanics, demonstrates its conveniently bendy laws of physics, spawns a bunch of oblivious passing pedestrians and then just says “Alright. Now go nuts!” This playful dynamic can easily contradict the cinematic logic generally tied to a narrative. One developer that makes the dynamic work to their advantage, however, is Rockstar.

GTA, Bully and Red Dead Redemption are not only ridiculously fun games but also contain some intelligent, and deeply fascinating, narratives. Rockstar achieve this by doing the last thing you might expect: by leaning in to the preposterousness of the worlds they create. Every city and environment in a classic Rockstar game serves as a character in itself: an intellectual yet hilarious parody of reality; brimming with life, detail and lots of satire. Most importantly, however, the developer never fails to populate these places with the most absurdly entertaining characters only the minds at Rockstar can come up with. For the most part, the missions forwarding the narrative are designed primarily to ensure you have more fun than you thought possible, but every now and then an emotional moment creeps up on you and you realise you care a lot more about these characters and their goals than you thought you did.

Role-playing and having a ‘say’ in everything – Bioware

Bioware stands as another stellar advocate for narrative. OK I’m not sure what happened with Andromeda but last generation’s Mass Effect trilogy remains to this day one of my favourite narrative experiences of all time. Not only did the developers and lead writer Drew Karpshyn create one of the most immersive and fascinatingly detailed playable universes in gaming history; they also proceeded to grant the player a unique level of agency in the creation and development of the lead character. Many RPGs allow you to construct your protagonist almost from scratch – customising everything from gender and facial appearance to background info, personality and demeanour in conversation. Mass Effect, however, was the first game that allowed you to do all this whilst also providing your character with a voice. The time and effort required to write and record 3 separate lines of dialogue for almost every conversation choice, with both a male and female voice-actor, must have been staggering. The pay-off was an unwaveringly involving and wonderfully personal narrative experience. Whether your Shepard was a classically heroic, disciplined military type; a roguish and ruthless all-round badass, or a complex mix of the two was completely up to you. And don’t get me started on the wonder that is save-importation! Seriously don’t, I’ll never shut-up…

Now I know what you’re thinking: “how can someone write an article about video-game stories and not mention Naughty Dog or Irrational?” Well I suppose for the same reason I wouldn’t read The Lord of the Rings in one sitting: it would take me kind of a long time. An examination of these great developers and their uniquely crafted stories must therefore be tabled for another time. To be continued…