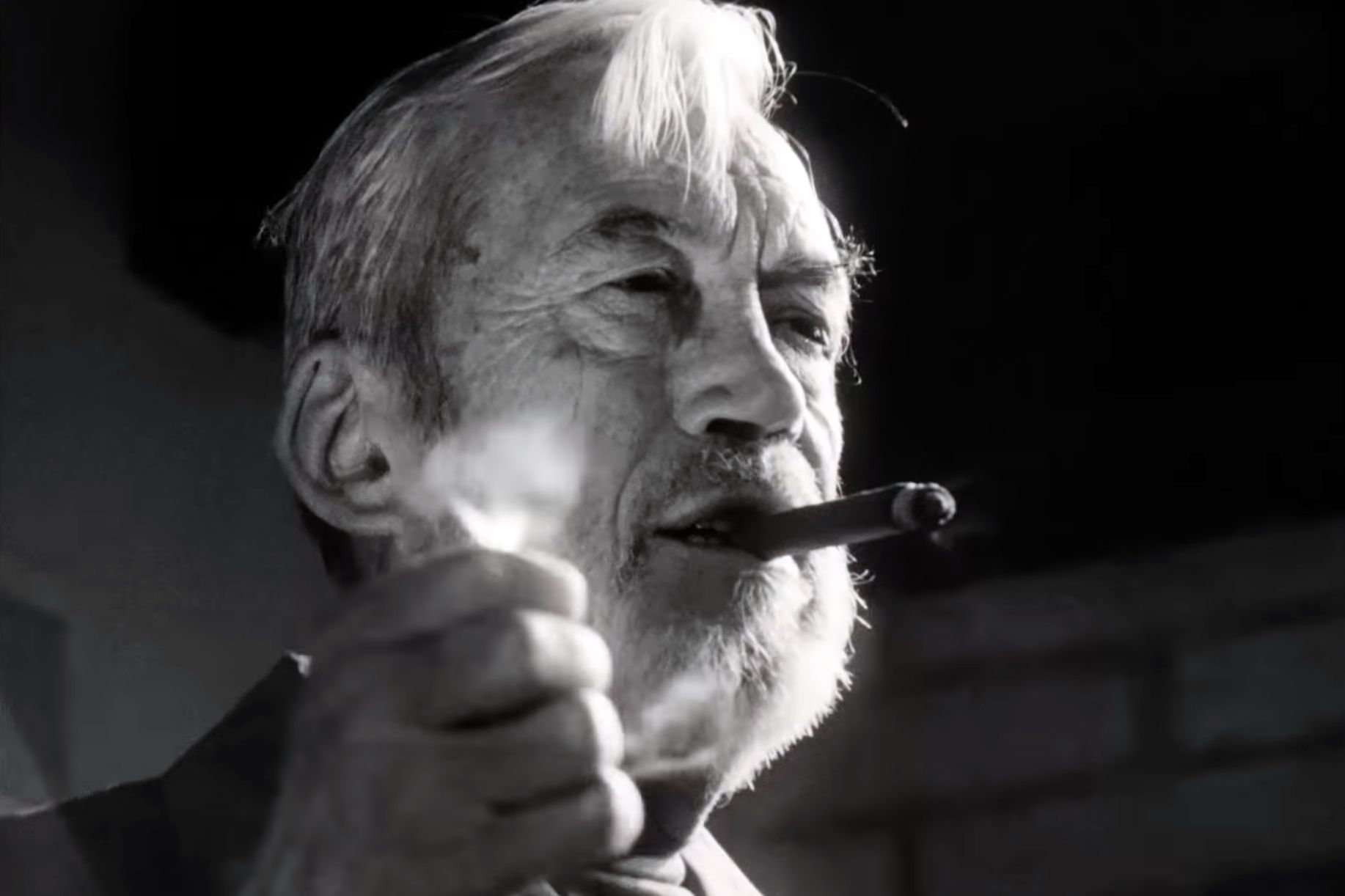

Well, this is pretty weird. In the year 2018 we are receiving a film from Orson Welles, the director/actor responsible for several of the most celebrated films of all time including Citizen Kane, The Third Man, and Touch of Evil. But despite Welles’ significant legacy, his film-making was complicated by an inability to find financial success, and while his films are now exceedingly well-regarded, he has a relatively small filmography due to his financial woes. By the end of his career major studios completely avoided him, and while The Other Side of the Wind was shot throughout the 70’s, and editing work was done throughout the 80’s, when Welles died in 1985 it seemed as though it would never see the light of day. But that changed in 2014 when the rights to the footage was acquired by Royal Road. On November 9th 2018 it was finally released on Netflix, marking roughly 43 years since its principal photography concluded.

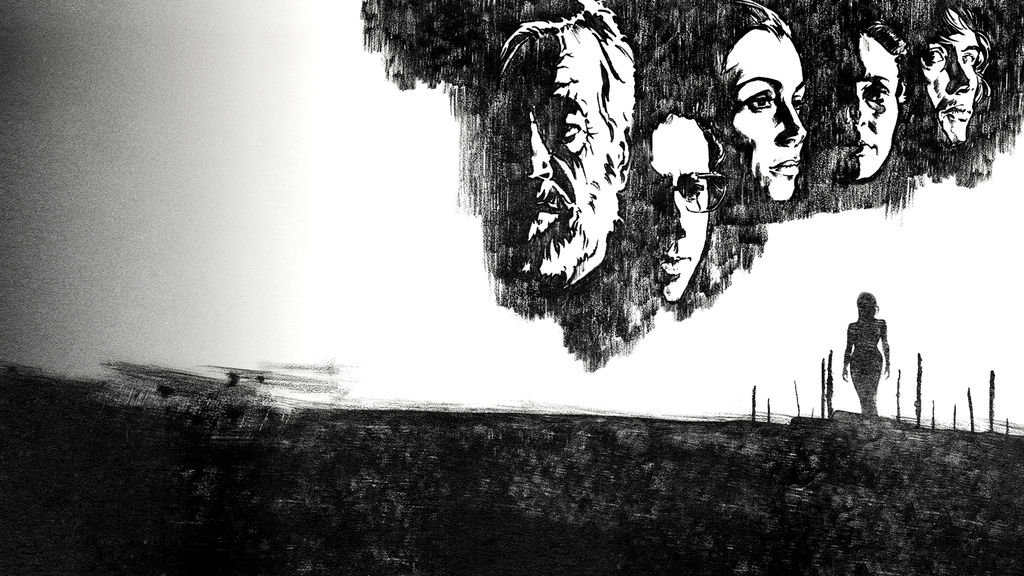

Thankfully after decades of existing in a mythical limbo, the end result is a hilarious, and often hallucinatory mockumentary that represents a master looking critically at his legacy and his own craft. The film begins with a monologue that explains that we are about to witness “documentary” footage taken of the legendary but aging film director Jake Hannaford the day before he died. It is his birthday, and to celebrate he plans on showing an initial screening of his comeback flick, The Other Side of the Wind. We are immediately greeted with the frantic cacophony that follows this auteur, his party functioning equally as a marketing stunt and an indulgently solipsistic affair. Surrounding him are quipy film makers that constantly demonstrate their acerbic wit, comedically pretentious film critics that endlessly berate Hannaford with esoteric questions (“What is the fundamental aesthetic distinction between a zoom and a dolly?”), and his clique of “friends” that he shares complex relationships with.

The framing device of a mockumentary allows Welles to lampoon the industry that he had dedicated his life to. From its depiction of film critics as mostly a band of socially awkward dweebs, to how it displays the deification of the director by his cronies, to all of the pomp and circumstance that swirls around Hannaford’s every action, Hollywood is portrayed as something of a circus. Through the director’s screening of his new movie, we are presented with a film-within-a-film structure, allowing for Welles to play with the form of European art-house films of the period. The fake picture is an aesthetically dazzling haze of gratuitous nudity, light sprinklings of plot barely diverting attention from its shallow nature. This banal showing simultaneously works as both a criticism of this brand of film making that values style over substance, while also simultaneously drawing inspiration from the visual splendor of this movement.

And the film being terrible is also kind of the point. Although the aging visionary is revered in his own circle as something of a god, the man is more defined by his fallibility than anything else. His constant witticisms thinly veil his abject desperation to remain relevant, and while he is never outright mocked, the character clearly draws from Welles’ own insecurities as a creator. But The Other Side of the Wind’s meta-textual nature never feels too distracting, and by drawing from his own experiences, Welles engenders many of the characters with a degree of specificity that is often lacking from satire. Hannaford’s previous pupil, Brooks Otterlake is a financially successful director who shares his mentor’s biting sense of humor, but ultimately still craves the approval of his faux-father figure. Even the film critics who mostly exist here to be the butt of jokes and to offer ridiculous Freudian comparisons, even this group has a have a worthy representative in the form. Juliet Riche, an acclaimed critic, seems to be one of the only people in this story that is able to cut through all of the artifice and offer legitimate insight into the circumstances at hand.

The mockumentary format is delivered through claustrophobic camera work, capturing the notion that at least for this night, virtually every moment of these people’s lives is being captured on film. The introduction captures the distressing nature of this entourage with shaky-cam and disorienting closeups. Some shots are in color, some are not. Some have more traditional compositions, while others imitate the effect of being filmed on the fly. As a result the presentation fits well with the actual stitched together nature of this picture, as modern editors had to stitch together large portions of Welles incomplete work. On top of representing the unending pressure of fame, the camera work is often used to accentuate the humor. In one particular visual gag, a lens zooms in and out while being inter-cut with the squirms of an uncomfortable member of an interview, directly representing the cloying presence of the paparazzi.

While The Other Side of the Wind is meant as satire, it’s characters come off as more than caricature, capturing the cynicism that these creative types wield to insulate themselves from the from their self-flagellating line of work. In Hannaford we see the weariness of a man that has dedicated the better part of his life to film, and the toll that it has taken on him. It’s a story that functions largely off of its ability to convey these notions through its sharp dialogue and performances, with its found-footage aesthetic tying in nicely to its themes regarding the death of golden age Hollywood by offering a clear visual foil to old-school film-making. Although the intense bitterness the film exhibits can be overbearing at times, Welles’ presentation of the hubbub surrounding the film industry feels exceedingly prescient considering the modern world’s predilection towards the hum of reality television and our collective obsession over the lives of stars. Welles’ final film may not be the most sentimental picture, but is quite a nice gift from the grave indeed.

Rating: 4/5