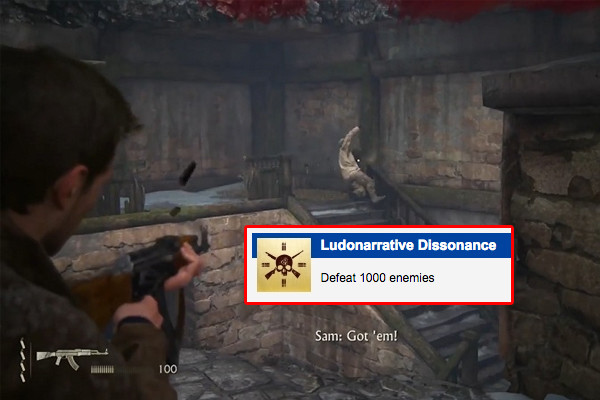

We’ve all seen it before. Our game stars a charismatic protagonist, one that could generally be described as a good person. In the cut-scenes or dialogue they are largely a moral figure, one that we are comfortable playing as. However, once the combat begins something happens. As hordes of human enemies flood the screen, our main character, under our control, gleefully murders them all. Suddenly our paragon of virtue has awkwardly crossed the line into becoming a mass killer, with little comment from the narrative with how this is at least mildly troubling. The classic modern example of this is the Uncharted series, in which the charming Nathan Drake routinely kills hundreds of pirates all the while being spun as a roguish hero.

The term for this disconnect between gameplay and story is known as “ludonarrative dissonance”. ‘Ludo’ refers to the ludology, or the study of games, while narrative obviously refers to plot and themes. This phrase was coined by Clint Hocking, a game developer who was a creative director at Lucas Arts. In its original context, Hocking was using the term to refer to the inconsistency between the themes Bioshock’s plot presented, compared to its gameplay loop.

*Bioshock Spoilers*

Hocking argued that while the gameplay and setting of Bioshock forced players to take sides in regards to Randian Objectivism, the proceedings of the plot completely undermined this by revealing that the player character’s “choices” were a complete mirage. While it’s central theme regarding the destructive power of greed was conveyed in its setting and in gameplay through the choice to harvest or spare little sisters, the player never has the option to act out of self-interest in regards to the central plot.

*Bioshock Spoilers end*

It’s important to note that in its original context, the term ludonarrative dissonance was applied to an extremely specific example in a single video game. Hocking was arguing that in Bioshock, elements of the core gameplay were fundamentally at odds with the game’s core themes. Since Hocking’s blog post, the term has been spun out to refer to the general dissension that often occurs between gameplay and story. A glance at the nature of etymology shows that language is a fluid thing, and considering this I will be using the term in its newer mutated context.

Whether or not Bioshock has a narrative breaking case of ludonarrative dissonance is the topic of another discussion, but Hocking certainly made a good point that a lack of consistency across all facets of a game can be jarring. As gamers, we’ve internalized this logic as acceptable over time, particularly because for the majority of the medium’s existence gameplay has been prioritized over story. When your protagonist is nothing but a vague cliche, and the plot boils down to “kill those aliens” or “save the princess”, there’s no narrative to clash with in the first place. This problem is mostly a modern one, arising out of an increasing sophistication of the ideas that games present, as well improved graphical fidelity.

One game developer who seems completely fixated on addressing this issue is Yoko Taro, the creative director behind Nier and a lead writer/creative director on the Drakengard series. The original Drakengard begins as a fairly standard JRPG action hybrid, allowing the “good guy” protagonist to kill large hordes of enemies in typical video game fashion. However, as the game nears its conclusion, it’s revealed that the reason our protagonist is able to commit these acts of mass murder is because he is actually a sadist who enjoys hurting others.

It’s unsurprising that Nier: Automata, Taro’s latest, is on the of most thematically cohesive games ever made. Automata proves that the benefit of directly addressing ludonarrative dissonance is less about merely making the gameplay and story make logical “sense”, and more about ensuring that all of the interactive moments serve the greater vision of what the game is trying to say.

*Nier: Automata Spoilers*

In Automata the player is placed directly in the center of a cycle of violence, given half-truths and an incomplete picture to simulate the viewpoint of our main characters. Through limiting our information and gamifying violence, the player gets a sense of what it’s like to become inundated with the sort of propaganda that warps world views. This is the unique power of games as a storytelling medium, offering complete immersion through implicating us in the actions of the player character.

*Nier: Automata Spoilers End*

While this type of approach certainly seems to unlock the latent potential of interactive media, it feels somewhat unfair to state that a game narrative “doesn’t work” if it breaks conventions of ludonarrative dissonance. For instance, does Uncharted 4‘s disconnect between its’ gameplay and storytelling completely ruin its central theme of rectifying a lifetime obsession with chasing glory? At least personally, I didn’t find the disconnect between the third person shooting combat sequences and the story completely game breaking. After all, Uncharted is drawing from swash-buckling adventure stories, like Indiana Jones, which generally have a high body count anyway. However, unlike ludonarratively cohesive games like Automata, every moment I spent mowing down bands of pirates was not a moment that was forwarding the narrative, an issue which was exacerbated by the middling combat encounters. It’s not that the elongated shooting sequences completely undermine the core concepts of the story, they just don’t further them, limiting the full potential impact.

An issue with video game plots in general is that the cadence of the gameplay dictates the flow of the plot. Endless streams of MacGuffins and vague objectives push us in one direction or another. Stories get awkwardly elongated, large swaths of time dedicated to killing stuff with not much in the way of narrative justification. This is an incredibly difficult problem to solve in big budget games that want to push innovative, engaging mechanics above their story and ideas. The recently released God of War largely side-steps this problem through pairing us with Kratos’ empathetic son for the entirety of their journey. Although a lot of the literal plot follows the same old get from point A to point B blueprint, the addition of a likable secondary character that questions the morality of the protagonist is enough to complement the action spectacle. Additionally the presence of Atreus allows the writers to constantly reiterate that this is a story about family, and more specifically about the morals and sins that are passed from father to son. The use of an unbroken sequence shot further melds the divide between playing and experiencing the story.

Considering that until recently the vast majority of big budget games had their plot almost entirely segregated into cut-scenes, with gameplay sequences that mostly consisted of “kill this thing” or “go to this place”, it’s impressive that some large scale properties are finally either addressing or mitigating ludonarrative dissonance in a major way. Meanwhile, many indie games that are less focused on creating spectacle oriented gameplay entirely meld their two halves. Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please is an excellent example, “gamifying” the work of a border crossing immigration officer in a dystopian nation. It has puzzle sequences that require players to sift through the documents of potential immigrants, rewarding harsh vigilance over empathy.

While ludonarrative dissonance doesn’t always completely undermine a game’s narrative, ignoring the problem almost always diminishes the full potential of a work. Although I was drawn in by the depiction of Nathan Drake’s internal struggle with his glory-seeking ways in Uncharted 4, games like Automata or Undertale fully unlock the potential of the medium. Storytelling in games is still something of a herculean feat given the additional upfront engineering hurdles and design challenges that they present, but it’s exciting that we live in an era where it feels as though many developers are tackling these storytelling problems head on.